As I tap away on the first installment of a my little blog about mental health in music, I sit only a hundred yards or so from a Chinese restaurant in my little East Texas town where, legend has it, Mick Jagger was at one time known to dine on occasion with his former paramour, model Jerri Hall. Hall is or was the owner of a ranch in the general vicinity, according to local lore. In any case, while wondering if Mick and I may possibly have in common a love of the establishment’s sumptuous Pu Pu Platter, I find myself also musing upon the 1966 Rolling Stones classic, “Mother’s Little Helper.”

As I tap away on the first installment of a my little blog about mental health in music, I sit only a hundred yards or so from a Chinese restaurant in my little East Texas town where, legend has it, Mick Jagger was at one time known to dine on occasion with his former paramour, model Jerri Hall. Hall is or was the owner of a ranch in the general vicinity, according to local lore. In any case, while wondering if Mick and I may possibly have in common a love of the establishment’s sumptuous Pu Pu Platter, I find myself also musing upon the 1966 Rolling Stones classic, “Mother’s Little Helper.”This twangy two minute and 40 second tune is a scary short story of ennui and substance abuse set to music; complete with the trendy-at-the-time spooky sitar riff (which according to some experts may instead be a rather less-exotic electric 12 string guitar.) It tells the tale of the growing disenchantment of a mid-century suburban housewife and her descent into a rather tenuous pharmacologic subsistence. The mother sung of, it seems, has a doctor who writes her prescriptions for a “little yellow pill” even “though she’s not really ill. ” The listener meets the doleful protagonist at the point she has begun to rely more and more on this ostensible remedy for her world-weariness and to make it through her “busy dying day.”

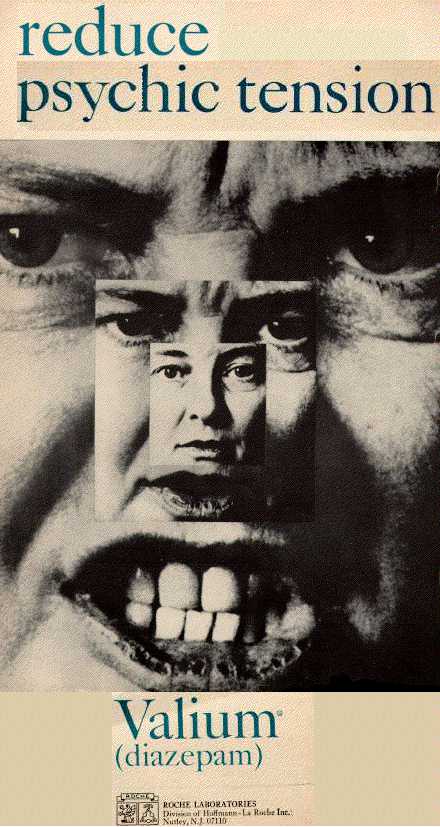

The medication Jagger and the song’s co-author Keith Richards mention by size and color but not by name can be pinpointed by those details, the song’s context and a little knowledge of cultural and pharmaceutical history as Valium in 5mg dosage. A blockbuster product launched in 1963, the same year Betty Freidan published her best seller The Feminine Mystique, Valium promised prompt relief from what Friedan’s book called “the problem that has no name.” The pharmaceutical industry and advertising wizards of the era took a shot at naming it anyway and came up with “psychic tension.”

As the song progresses, Jagger disdainfully warbles on about the mother of the title exceeding her dosage (“Outside the door, she took four more”) after pleading for what probably was an early refill (“Doctor please, some more of these”) and alludes to dark consequences if things keep on this way. And in point of fact, Andrea Tone, in her 2008 examination of America’s troubled love affair with tranquilizers post WW II, The Age of Anxiety, seems to feel that the lady in the song is a goner. The “busy dying day,” Tone suggests, is actually a day in which mother’s busy dying. However, absent co-ingestion of potentiating substances, medical literature finds benzodiazepine overdose to generally be associated with low levels of mortality. (Not that it is a “safe” drug to consume counter to a prescriber’s instruction by any means--no drug is.)

But nevertheless, the wife and mother (the primary social constructs that much of society at the time, and probably she herself would employ in her cultural categorization) sounds as though she is falling victim to the all too common misconception that prescription drugs are harmless. Since her trusted doctor blithely prescribes her little yellow pills, and he in fact keeps giving her more, they must by definition be safe. If a little is good a lot is better.

While the song is a fictional vignette, it is perhaps rather representative of the negative potential of the power differential between physician and those in the patient role (particularly suburban homemakers) in the period before such considerations were even a matter of concern in care delivery. In a 1979 qualitative study seeking to determine social meanings of tranquilizer use, researchers Ruth Cooperstock and Henry Lennard identified “the culturally accepted view that is the role of the wife to control the tensions created by a difficult marriage” and an accompanying “implicit” acceptance “that drug use is justified in order to accomplish this.” All gender politics aside, mother’s negative feelings do abate for a time after the pills are taken. It’s just that she’s swallowing more and more pills, more and more often.

Yet sooner or later the haze lifts, albeit briefly, and there remains, as there always remains, that same unappreciative spouse, those same unyielding children and that more recently arrived acrid stench of burnt steak and cake resulting from stuporous attempts at cookery. All of which drive her to the distraction of her little yellow pills and further along the road to overdose and subsequent rest cure in a nearby sanitarium (this song is perhaps backstory for The Stones’ earlier hit, “19th Nervous Breakdown”). After all that there may indeed be “no more running for the shelter of a mother’s little helper,” at least not in the form of diazepam. The song’s good doctor would probably just scribble for something newer and “safer” when mother’s discharged with a clean bill of health. After all, she “isn’t really ill.” She’s just suffering from an unwanted buildup of psychic tension that can be washed away with the right chemical, as is the waxy yellow buildup on her lime-green kitchen floor.

The underlying human desire to avoid or extinguish psychic distress is of course much older than even The Rolling Stones (formed circa 1962). From the beginning of time, people in pain have sought what frequently turn out to be illusory or half-measure methods (e.g. a bottle of little yellow pills) to escape it. Often doing so to their greater disadvantage. Another Pop (psychology) Icon R.D. Laing, who somewhat coincidentally gave refuge to a confused gentleman who believed himself to be Mick Jagger at one of his “therapeutic communities” in the 70s, had this to say about such evasion, “There is a great deal of pain in life and perhaps the only pain that can be avoided is the pain that comes from trying to avoid pain.”

File under: Musings and Reflections