“It’s easy to lie with statistics, but it’s hard to tell the truth without them.”

—Andrejs Dunkels

Nearly every therapist I ask says that they regularly monitor the progress of their clients. Besides, why wouldn’t therapists check in and ask for verbal feedback?

Yet, given our clinical expertise, how is it that the assessment of our client’s progress is often inaccurate? In addition, why is it that therapists’ view of the process of clinical engagement is less predictive of outcome than that of their clients?

I believe this is because of our over-reliance on clinical intuition. We are trained to listen and take heed of our gut sense. Don’t get me wrong; intuition is critical, as scores of studies on this topic will attest (see Gary Klein’s body of work). Yet, relying solely upon clinical intuition is like asking a physician to treat a patient without the use of a stethoscope, a thermometer and the results from a bloodwork.

From Assessment Thinking to Conversational Thinking

It’s time that practitioners learn to use outcome measures and engagement tools as part of regular clinical practice. And not merely as assessment tools, but as conversational ones. And to make this happen, clinical supervisors need to be on-board, trying it for themselves (especially if they are also practitioners), learning as much as they can about how to integrate measures as part of treatment and then teaching them to supervisees.

I once had a supervisee who wanted help getting “unstuck” with a client. We talked at length about the presenting concern, clinical background and what she had previously tried. The supervisee and client had just completed their 4th session when the therapist described that “things aren’t moving.” In other words, there was no discernable clinical progress.

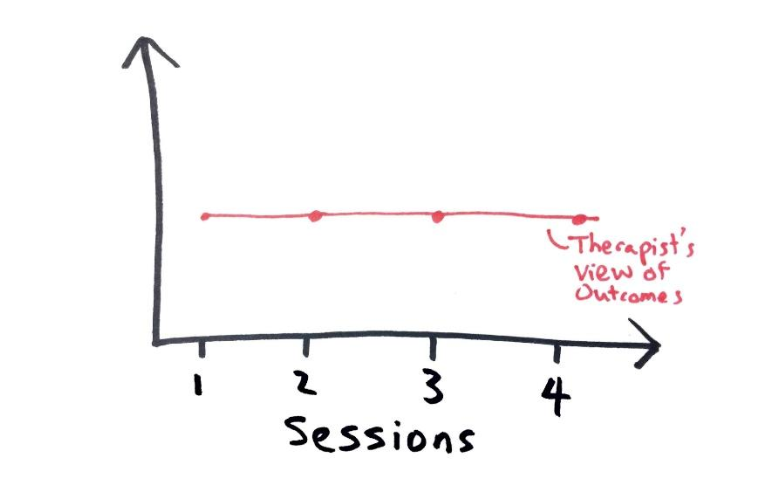

Therapist View of Progress in the First Four Sessions.

I asked if she used any form of measures in her work. I learned that this therapist had been using outcome and alliance measures in her practice, but had not reviewed the graphic description of those measures. She was using the measures only because the management team insisted that she do so. I suggested that she bring the graphs to our next supervision meeting.

Here’s what the graph looked like:

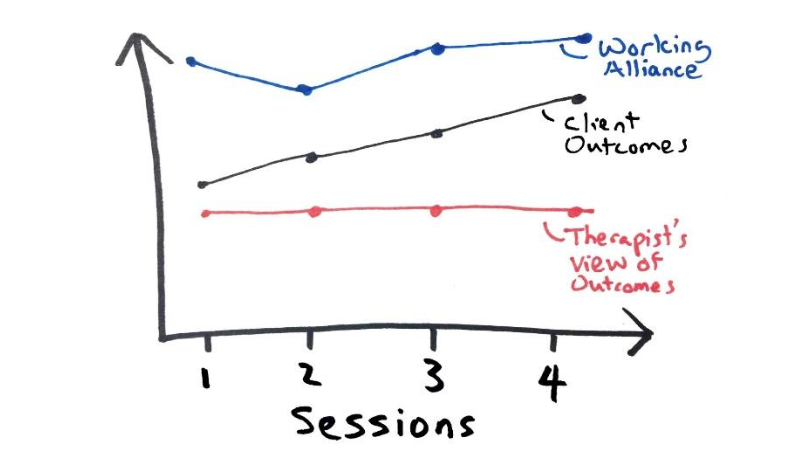

Therapist View of Progress Alongside Client’s View of Session-by-Session Progress and Engagement

Even though there was a dip in the alliance at the 2nd session— a rupture from which the clinician was able to bounce back—contrary to her perception, this client’s experience suggested that outcomes were gradually improving. Not only was the therapist’s appraisal off the mark, but the plans we had devised with which to repair the perceived rupture were not right for the context. It was like wearing winter clothes in anticipation of being in the frigid Alaskan north, but instead finding ourselves baking on a beach in Bali.

We went back to the drawing board. We spent time working through the supervisee’s uncertainty and anxiety about her perceived lack of progress, while keeping in mind that the client was clearly perceiving and experiencing benefit from the engagement. As it turned out, the therapist was torn between addressing the psychiatrist’s referral concern of OCD, versus the client’s implicit desire to improve his relationship with his father. Thankfully, the therapist maintained fidelity to the client’s rather than the psychiatrist’s concerns.

In supervision, we re-focused our attention around attending not only to this particular client rather than the referral source, but how to do so with future clients so we could also address the perceived need of their referring sources. More importantly, the therapist needed to unpack and clarify some inferences about what she was doing and thinking that might have contributed to this gradual improvement, despite thinking that none was being made, so that she could continue doing so.

In this instance, thankfully, the client was improving. However, the opposite can just as easily happen, i.e., when we think that improvement is being made, but the client reports that “things aren’t moving.” When intuition and real-time data are either out of synch with each other or not taken together into consideration, clinicians (supervisees in this case) are prone to self-assessment bias. While we are re-playing mantras in our heads that say, “The clients will get worse before they get better,” we quickly realize that our client has dropped out of treatment.

Quick tip: In clinical supervision, make sure that supervisees bring in graphs of the client’s outcome and engagement. This is one critical way to privilege the client’s view of progress and engagement across time, while incorporating it into supervision. In turn, we can also monitor the impact of the “backstage” conversation of supervision on client outcomes.

But Why?

Here are two primary purposes for weaving ongoing measures into therapy and using them in clinical supervision:

1. At the Client Level

a. Guide the treatment process: “Are we on-track, or are we off-track?”

b. Use the feedback to feed-forward: Real-time feedback allows you to tweak the service delivery to fit each client, each step of the way.

2. At the Therapist-Level

a. Effectiveness: If used systematically, session-by-session with every client, the

therapist can figure out the nagging question at the back of all our minds: “How

effective am I?”

b. Individualized Development: Once you figure out where you are with the help of a

supervisor who is attuned to this type of process, you can start the journey of figuring out

“where you need to go” in your individualized professional development. (More on this in an upcoming blog post).

There may be many reasons not to use routine outcome measures in therapy, and only a few good reasons to do so. Personally, I am not a fan of numbers. The irony is not lost on me being Chinese and failing math (and Mandarin) in my early years. Besides, it is not as if therapists around the world need another thing to pile onto their existing and ever-growing paperwork! Yet, the benefits far outweigh the costs of not integrating some form of measures—tracking what is of value to the client.* A groundswell of studies now show that the use of measures such as a real-time feedback tool not only reduce deterioration in client well-being by a third, but doing so cuts drop-out rates by half, and as much as doubles the overall effectiveness of therapy.

The use of intuition without high-value data** is like trying to drive in a foreign country without a GPS or an old-school map. It’s possible to still get to your pinpointed destination—especially if your sense of North is better than mine—but the journey is likely to be mired in and derailed by unwanted detours. On the other hand, the use of data in the absence of intuition is like blindly following your GPS into a ditch, when the new road, which is just to your left, has simply not yet been updated into the system.

The knowledge gained from the marriage of data and clinical intuition contributes to a type of dialogue that is richer and aids clinical decision-making. Sometimes, client-reported data confirms what we intuit. Other times, the data contradicts our gut sense. The point of monitoring progress and weaving it into clinical supervision is not to defer all judgement to cold and unintelligent data. The point is to wrestle with this tension in order to see and think more clearly.

To learn more about becoming a better supervisor, check out the in-depth online course, Reigniting Clinical Supervision.

Notes:

*It is highly possible to be measuring something systematically that is not relevant to your client. For instance, capturing data without integrating the measures to inform the treatment process. Second, dogmatically using a symptom-specific measure that may not make sense for all your clients. This is why it makes more sense to be capturing information about a person’s global wellbeing.

** Data is only valuable when you are not valuing whatever you measure but measuring what is of value.

File under: The Art of Psychotherapy