As a clinical supervisor, it is vital to help our supervisees move into their zones of proximal development, or that learning/experiential space just beyond their comfort zone (CZ)¹. But in order to do so, the supervisee’s current realm of abilities and limitations needs to be well-defined. This entails figuring out when they are at their best, how they conduct a typical session, what parts of them shines through, and how effective they are in aggregate. In other words, supervisors need to first help their supervisees figure out the bounds of their CZ so they can begin to push beyond it.

Supervisees must regularly pose questions to themselves such as, “What am I used to doing in sessions?” or “What did I do well” or even ”Was there something I did or said that stands out which might have contributed to the development of my client’s progress?”

We get comfortable with what we do well. Naturally so. The only problem is, if we fail to take the steps, our comfort zone can become our hell zone. What was once helpful with a particular client or type of client can become problematic or ineffectual. Think about your parents. If you were blessed with good enough parents when you were little, imagine if they used the same cuddly warmth and nurturing tendencies with you when you were a teenager. That wouldn’t have worked. You would have rebelled with angst. Past attempted and seemingly successful solutions can become today’s problems.

Here’s one of the axioms I have come to rely upon which defines the bounds of my current comfort zone (CZ): Provide clear and playful strategies to clients at the end of each session.

Over the last few years, I found myself drawn to being more playful and improvisational. This wasn’t how I used to be. I was constantly plagued with the question, “Am I doing this right?” Then I begin to realize that once I freed myself up to be more playful, I felt more flexible and less certain. This new mindset was unsettling and shook things up for me.

Other practitioners’ CZs that I’ve come across are founded in the following axioms:

“Be attentive and follow a clear treatment protocol.”

“Explore a person’s strengths and resources.”

“Develop clear treatment goals from the beginning.”

“Able to attune and empathize with my clients.”

First, and as noted above, it is critical that as supervisors, we help our supervisees to regularly ask themselves, “What did I do well?” “What stands out that I contributed to the development of my client’s progress?” This shall be your comfort zone.

It’s important to base your supervisee’s LZ on two critical pieces of information:

1. Their overall clinical outcome data, and

2. Feedback from a coach who knows their work.

By looking at the supervisee’s aggregated outcome data, you can begin to spot any glaring patterns. For example, early in my profession, I was shocked to find out that my own clinical outcomes for clients presenting with relational issues were the poorest compared to other presenting concerns, even though I was steeped in the systemic perspectives. Your role as a supervisor is to point out what the supervisee can’t see and lead them in the right direction.

Here’s my own current LZ as a therapist: I would like to learn to help clients face the feelings that they avoid. It’s so easy to continue validating and, as a result, getting lost in the interaction with my clients, while missing the opportunity to go deeper and help them with their difficult and painful emotions.

Other common LZs that I’ve come across in clinicians include:

“I would like to learn to improve the way I start my sessions.”

“I would like to learn to improve the way I close my first sessions.”

“I would like to learn to improve the way I elicit feedback at the close of a session.”

For instance, if your supervisee’s data suggests that many of their clients come only for one session and drop out after that, you may be tempted to state that their LZ is “…to improve my return rates after the first session.” I see this more as an outcome goal. That is, you want X to influence Y, and “Y” is your outcome goal. In this case, you need to specify X and work on this.

Typically, when practitioners try to identify their own learning objectives, they tend to identify theoretically specific areas to work on (e.g., how to better conduct two-chair work on the inner-critic; how to employ a solution-focused approach when working with exceptions). Meanwhile, after examining their aggregated baseline performance metrics (more on this in upcoming blogs) and watching samples of their sessions, what I often end up proposing that supervisees work on is more fundamental and maybe even less revolutionary (e.g., how they begin a session, how they develop an effective focus, how they deepen the client’s emotional experience and how they end a session).

Most therapists and supervisors I know are life-giving and affirming. However, instead of simply bolstering their esteem with praise and consolation (A common refrain that I hear supervisors give, “Well, your clients came back to see you, didn’t they?”) without actually helping them identify their learning zones, we are doing our therapists and clients a disservice.

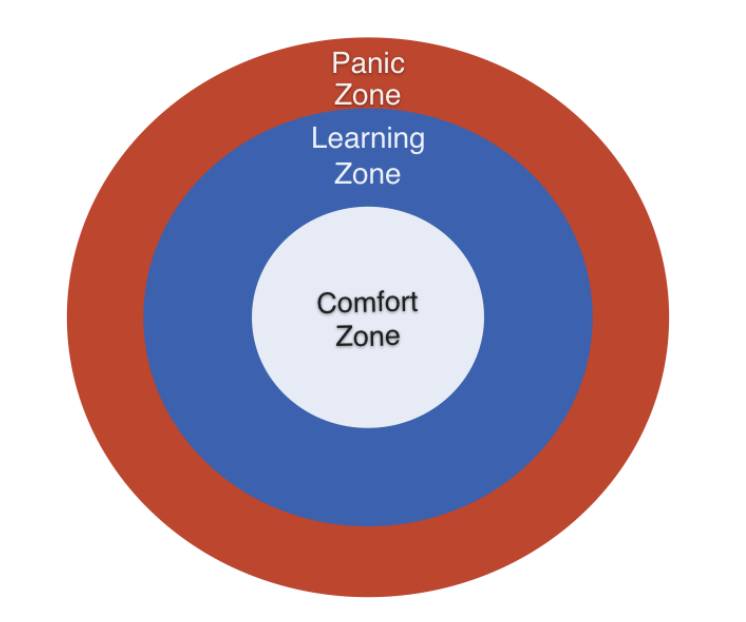

Here are some common Panic Zones self-statements that I’ve encountered:

“Trying to learn what my supervisor says I should be focusing on, when I do not fully agree.”

“I know I should be working on difficult emotions like anger, but I do not feel ready at this point.”

“I tend to take critical feedback personally.”

“I just do not have the time and energy for this.”

Our circle of development is not static; it’s dynamic. If there is movement and directionality in the supervisee’s development, what used to be learning zone material might evolve to into the domain of the comfort zone. Likewise, what was previously panic zone materials can shapeshift into the realm of their learning zone.

The aim of helping our supervisees in figuring out their boundaries of their comfort, learning and panic zones is to clarify, magnify, and guide your supervisee’s messy and non-linear of professional development².

In the next blog post, I will address the critical value of teaching your supervisees to systematically monitor their clinical progress and how to use it beyond simply an assessment tool.

P.S.: My collaborators and I know how hard it is to figure out the key learning domains that therapists can spend their time and effort to deliberately practice. This is why we turned to what cutting edge research has to tell us, deconstructing the therapy hour, and we developed a comprehensive guide called the Taxonomy for Deliberate Practice Activities (TDPA) (Therapist’s and Supervisor’s version) (Chow & Miller, 2015). This is expanded upon in our forthcoming book, Better Results: Using Deliberate Practice to Improve Therapeutic Effectiveness (Miller, Hubble, Chow, 2020). But for now, if you are interested to receive a copy of the TDPA worksheets, drop me an email.

References

Chow, D. (2017). The practice and the practical: Pushing your clinical performance to the next level. In D. S. Prescott, C. L. Maeschalck, & S. D. Miller (Eds.), Feedback-informed treatment in clinical practice: Reaching for excellence (pp. 323-355). Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association.

Chow, D. (2018). The first kiss: Undoing the intake model and igniting first sessions in psychotherapy. Australia: Correlate Press.

File under: The Art of Psychotherapy