Email or Call: 1-800-577-4762

NEWSLETTER

CONTACT US

The Anxiety Disorder Game

- The Anxiety Disorder Game

- Personifying Anxiety

- Shifting the Client’s Game Plan

- The Moves of the Game

- Standing Down--The Permissive Skills

- Going Toward--The Provocative Skills

- Wanting Habituation

- Skills Meet Challenge

- Score Points! Win Prizes!

- Social Anxiety Strategies

- Julie

- OCD Strategies

- Jai

- Jordan

- Vann

- Conclusion

The Anxiety Disorder Game

What causes someone to commit so strongly to the need to avoid doubt and distress?Imagine a man standing in front of an audience and suddenly being unable to think clearly enough to speak his next sentence, ?nally stumbling through, putting a quick death to his speech and walking out of the room in humiliation. It would be expected that he would worry about how bad the next time might be, even envisioning himself in a repeat performance. Picture a woman on a bumpy ?ight, unexpectedly becoming terri?ed of deadly danger, and not being able to calm herself until the turbulence ended. It would be no surprise if she avoided future ?ights anytime the weather seemed less than ideal. Consider a father su?ering from obsessive-compulsive images of choking his infant daughter. That graphic horror would compel any loving parent to avoid being alone with his child.

An almost instinctive reaction to these traumatic events is adaptation, however not all adaptation is psychologically healthy. Unhealthy adaptation could include exaggerated worries, anxiety, and inhibition of the capacity to act on their environment in an attempt to create a feeling of safety or avoid these threats in the future. If these maladaptive responses continue then the person will develop an anxiety disorder. If we look more closely, it seems that many of these same people begin to develop a general maladaptive framework for operating in the world. Safety becomes of paramount importance. The person with an anxiety disorder believes that losing control of their feelings or circumstances can come quickly and easily. Given that belief, avoidance is an easily adopted strategy. When the person with an anxiety disorder avoids, vigilance becomes their primary safety behavior. Once they recognize a potentially troubling situation, they want to end it immediately. If their heart starts racing and their head gets woozy, they ?ght to get rid of that discomfort as fast as they can. If the discomfort cannot be stopped by escaping, then they begin what they think is a problem-solving process, however this is not problem-solving but only excessive worry.

The goals of worry make perfectly good sense given the crippling anxiety people have experienced. The problem is that this strategy only serves to increase the problems that they are designed to prevent. When we resist the physical symptoms of anxiety, we ensure that anxiety will continue. The adrenals secrete that muscle-tensing, heart-racing epinephrine through the body, the brain matches it, and we will become more anxious.

Using worry to solve problems will back?re. Worry is a problem-generating process since it causes people to think more about how things might go wrong than about how to correct di?culties.

Two other tendencies contribute to their struggles. Anxious people don’t want to make mistakes, believing they will have dire consequences. They also don’t want to feel any distress, and the goal of the worry is to stop or avoid uncomfortable symptoms as soon as they arise. That message—“don’t get tense!”—is a sure way to create a self-ful?lling prophecy.

All these tactics together become a powerful force structured within a powerful fortress that drives the decisions of anxious people. They follow a belief system—a schema—that tells them how they should respond to doubt and distress. The belief systems of some clients are so strong that they ride roughshod over the therapeutic strategies we employ. No matter what instructions and techniques we give clients, their overriding unconscious and usually conscious, goals are to end the doubt and distress.

Much of my understanding of these drives, to avoid discomfort and seek certainty at all costs, grew out of years of failures. If I began treatment by teaching someone brief relaxation skills, they would incorporate those skills into their strategy of trying to keep the anxiety at bay. If I o?ered assignments counter to their defensive belief system, clients would not follow-up on the homework, or they would become confused after leaving a session. If I were especially e?ective in persuading them of the importance of practicing skills, they would simply drop out of treatment.

For over twenty-?ve years I have gradually modi?ed cognitive-behavioral treatment that included relaxation training, breathing skills, cognitive restructuring and exposure strategies, to address the special issues created by anxiety disorders. By 1992, for instance, I drew on dozens of discrete techniques, some old standards along with some new procedures, to help my panic disorder clients alleviate distress. But as the years passed, I felt that technique alone was insu?cient. My experience taught me that if we focus on techniques without ?rst challenging their beliefs, then their fear-based schema will overpower our suggestions.

Personifying Anxiety

Anxiety disorders have a clear strategy to dominate. They condition the person to three contexts: the situation that stimulated their fear, the fear reaction itself, and their use of avoidance as a coping mechanism. The person creates a defensive relationship with each of these: to become doubtful and anxious when approaching that situation, to feel threatened by their anxiety and want to get rid of it, and to avoid when necessary to stay in control. These strategies are incorporated both into the neurology and the belief system of the person. Each interpretation and behavior in response to anxiety is directly linked to this frame of reference. I use a cognitive approach in which most of the therapeutic time is spent addressing clients’ relationship towards the anxiety, not the anxiety itself. My goal is to teach clients therapeutic principles powerful enough to o?set their faulty beliefs that they must battle anxiety and must become relaxed again quickly. Clients learn to mentally step back, away from a poor quality interpretation of the situation (“this is a threat”) and a failing strategy to respond to it (“I must stop it”).In most ways, this approach matches the standard cognitive-behavioral protocol. However, this is also where I begin to diverge from some standard CBT strategies. To win over fearful anxiety, I believe the therapeutic strategy must meet the following conditions.

1. It must be able to compete with the power of fear and distress. This includes creating an emotional shift that is strong enough to match the drama of anxiety.

2. It needs to have a simple frame of reference that makes sense to the client. My most consistent task with anxiety clients is to keep a clear-cut message at the heart of our discussions. The sharper I am about a few points, and the more emphatic I am about using them as guiding principles, the more successful I am at in?uencing the client’s point of view.

3. It needs to provide a clear system to follow, with simple rules that guide their actions during fearful anxiety. Otherwise, consciousness gets swallowed up by the fortress of conditioning.

4. It needs to permanently in?uence neurology or, said another way, their physiological reaction to anxiety.

5. It needs to involve tasks that they feel are within their skill set.

6. It needs to help them feel in control instead of out-of-control. Anxious people regard themselves as victims of the anxiety condition. I want clients to feel in charge, to see themselves as the subject, not the object.

7. It needs to be simple enough and available enough for them to utilize during a confusing, anxiety-provoking situation.

Shifting the Client’s Game Plan

Anxiety disorders play a mental game and they create a game board with rules stacked in their favor. Anxiety wants to distract us by getting us to focus on the content and then to attempt to prevent problems being solved within that content area. For instance, in OCD the content is the possibility of causing harm to self or others through carelessness. In generalized anxiety disorder, it is worry about health concerns, money, relationships or work performance. In social anxiety it is the fear of criticism or rejection from others. This is a clever misdirection, since the true nature of the game is the struggle with the generic themes of doubt and distress. The end result is that the actual problems and solutions to the problems that drive the anxiety are not clear to the client.The disorder only wins if clients continue to play their expected role. If instead they can see the pragmatic opportunities for viewing their anxiety as a mental game, then we can begin to generate a framework to manipulate. Early in treatment I want to accomplish two goals. First, I want clients to recognize this distinction between the content they have been focusing on and the actual issues of doubt and distress that they must address. Second, I want them to take a mental stance and take actions in the world that are the opposite of what anxiety expects of them.

For instance, learning the skills of relaxation can be a great asset to recovery. But in training to win against anxiety, it is counter-productive to try to stay relaxed. It is best to seek out discomfort. This is one of the biggest early struggles for clients in treatment: to honestly take the stance of wanting to face the symptoms.

Fortunately, I wasn’t alone in creating such a new strategy. In addition to Eastern philosophy and principles of Zen Buddhism, my guides were Victor Frankl’s paradoxical intention, Paul Watzlawick’s reframing, which stems from the Mental Research Institute’s concept of second order change, and Milton Erickson’s fractionation and pattern disruption. Frankl’s work encourages the client to generate the physical symptoms he most avoids. Watzlawick and his colleagues were the ?rst to de?ne reframing as altering the perception of the problem, the solutions and client resources in such a way as to reinforce therapeutic interventions. Erickson’s fractional approach and pattern disruption aim to make small changes in the pattern of client behavior and the external circumstances instead of opposing the behavior and circumstances.

The Moves of the Game

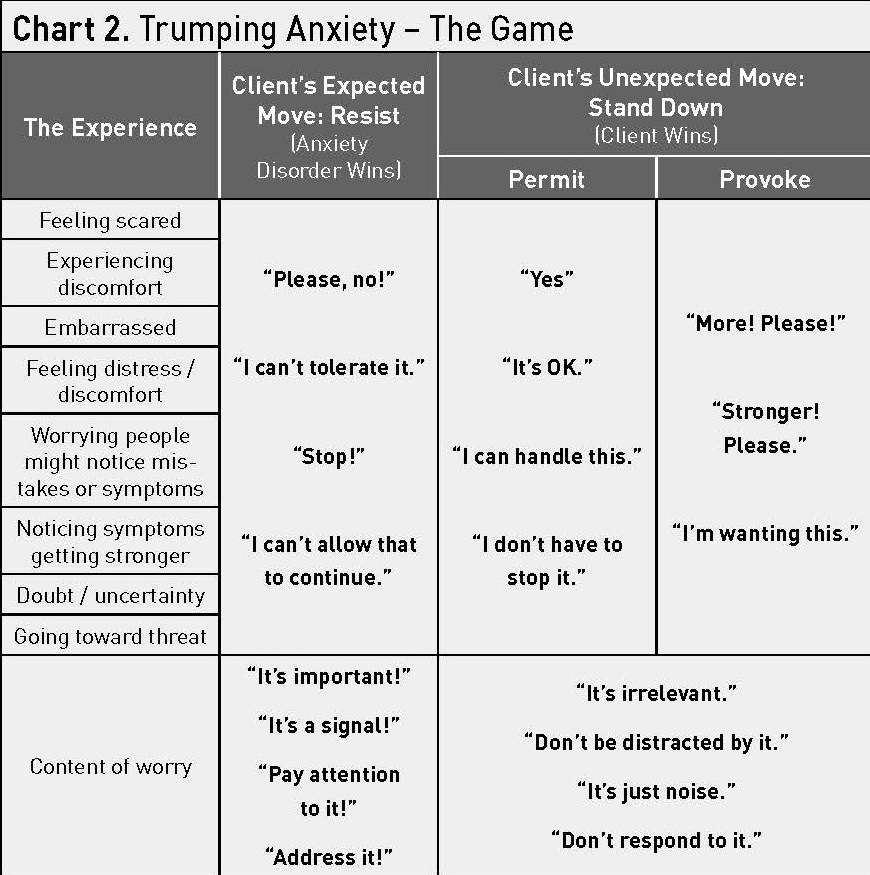

There is an existential game to learn when dealing with anxiety symptoms. People make a judgment that the symptoms of anxiety are unwanted intruders and threatening enemies and they want the trouble to end. They keep hoping that one day they won’t experience any of these symptoms. Thus, they become trapped by their expectations. Existentially, there is no need for such judgment. The symptoms of anxiety disorders can simply exist, without being deemed good or bad. The anxiety disorder wins when clients judge the symptoms to be wrong and to be banished. In order to win over anxiety, they need to start by stepping back from their current experience, observing it and labeling it as acceptable to them in the present moment. Sounds simple enough in theory, and in the end, clients who recover will master this skill. They learn to stop playing the game by anxiety’s rules. But initially it takes all the clever persuasion a therapist can muster to unhinge clients from their old frames of reference.In Chart 1 you will see some possible responses to the symptoms of doubt and distress. Clients enter treatment in the position of resistance. In their most resistant position they say, ‘This is horrible. I’ll lose if this happens.” Even the stance of “I don’t want this to happen” gives anxiety the upper hand, because the mind and body will move into battle mode. Ideally, if clients can respond by saying “yes” to the encounter, and accept exactly what they are experiencing in that moment then they will be back in control.

.jpg)

But for many, the anxiety disorder has become so dominant that the client cannot make such a shift directly. As they attempt to accept their doubt and distress, they do so in order for that discomfort to go away. They are still oriented in their natural position of resisting the symptoms. They are more likely to say, “Let me try relaxing into this situation, and I hope this works, because I’ve got to get rid of this feeling.” The skills associated with permitting the symptoms to exist often allow the client to slide right back into resisting.

For those cases, the game takes a di?erent tact. We re-direct the attention of clients away from ?ghting the symptoms and purposely toward encouraging them. They choose to act as though the symptoms are good instead of bad, and something to be held onto, even encouraged instead of rejected. As clients master this game and learn its lessons, they develop the insights needed to shift toward a non-attached relationship. If they can endure the discomfort, they can learn. I created this framework of a game to help them endure and to teach them three overarching goals.

1) Step back and identify it as a game

The ?rst critical move is to step away from the drama, observe the event and name it. In meditation and in moments of relative quiet mindfulness, when the struggle isn’t great, you simply “step back.” You let go of your attachment to the thoughts. With anxiety disorders, in order to step back, clients must be able to label the event as one in which the anxiety is trying to dominate their mind. During threatening times, the drama is often too enticing to easily drop. They have already generated an automatic and rigid label that identi?es the situation as one in which they should become aroused and worried, for example, “This is a true threat to me.” I encourage them to replace this with any message resembling: “OK, the game’s on: anxiety’s trying to get me to ?ght or avoid now.”

This is one of the advantages of the game. By training clients in a speci?c protocol and by strongly reinforcing that protocol, they begin to look for opportunities to practice and they become more astute observers of these moments.

2) Stand down

Once they step back, they need to engage in a strategy to convey to their mind that it is time to “stand down.” The body and mind need help in backing away from the ?ght-?ight mode. If, in the face of a threatening situation, they attempt to say, “I want this experience,” then the mind begins to have a choice other than battle stations.

Standing Down--The Permissive Skills

The ?rst level of the game is to allow the anxiety to continue instead of trying to stop it.

This is manifested in the supportive statements, “It’s OK that I’m anxious,” “I can handle these feelings” and “I can manage this situation.” This approach has a paradoxical ?air to it that people often miss. You take actions to manipulate the symptoms while simultaneously permitting the symptoms to exist. With physical symptoms you are saying, “It’s OK that I am anxious right now. I’m going to take some Calming Breaths and see if I settle down. If I do, then great. But if I stay anxious, that’s OK with me too.” We attempt to modify the symptoms without becoming attached to the need to accomplish the task. This is a critical juncture in the work and the therapist must track closely the client’s expected move of, “I’m going to apply these relaxation skills because I need to relax in this situation.” No! While it is ?ne to relax in an anxiety-provoking situation, it is not OK to insist that you relax. That’s how anxiety wins.We reverse a common American catchphrase by saying, in the face of anxiety, “Don’t just do something, stand there!” When enough epinephrine pumps through the body then the brain yells, “Run!” Consciously overriding this impulsive message takes great courage, but pays great dividends. It di?ers from desensitization where we help the client gradually approach the feared situation under relaxed conditions. Here we confront their instinct to seek out comfort and encourage them to remain physically anxious and mentally as calm as possible. Instead of believing that there is something broken, they simply accept the status quo.Going Toward--The Provocative Skills

Many people consider acceptance a weak strategy in the face of the fortress of fear that has been built in the mind. They need to shift from the permissive stance (“It’s OK this is happening”) to the provocative stance (“I want more of this discomfort!”). Here they learn to encourage the symptoms instead of just accepting them. This strategy is extreme and can be thought of as ?ghting ?re with ?re. Fear is intense and acceptance is soft. Fear will trump calmness and acceptance every time. I help clients shift to an attitude of provocation that is equally as powerful as, and can compete with, fear. I teach them to use their willpower and conscious intention to seek out an even more rapid heartbeat, to encourage their feeling of contamination to grow even stronger, or to hope someone will notice their hands shaking.Why this line of attack? Because we want to interrupt the dysfunctional pattern in the most e?cient way possible. The straightforward way, using acceptance, is not necessarily the most e?cient way because it tends to be susceptible to the clients’ dominant paradigm of resistance, for example, “Let me try to relax here and I hope this works, because if I panic that will be awful!” Consciousness only has so much attention at any given moment. During an anxious moment, I encourage clients to commit themselves to play the game, and to focus their limited attention on following the rules: try to get anxious on purpose by encouraging symptoms. If they will bring their attention to the task of encouraging, even cajoling symptoms to become more uncomfortable, or for doubt to grow exponentially, then they automatically withdraw attention from their fearful goal of ending the doubt and distress.

When I suggest homework activities to clients, I use expressions like, “how about playing with this move?” and “perhaps you can fool around with these responses.” I imply that these strategies are malleable and temporary: “What do you think about just experimenting a few times with this move and see what happens? We can talk about it next time.” For some, we will literally play a game in which they score points for various types of responses to their worry or anxiety, or they will have to pay a consequence when they avoid or engage in some ritual to help themselves feel safe instead of threatened. An example of this strategy can be seen in the case of Samuel. One of Samuel’s fears was that he might unknowingly have cuts around his ?ngernails and cuticles that would expose him to the AIDS virus while shaking hands at work. Throughout the workday he conducted brief checks of his ?ngers. I gave him the following assignment:

- Go to the bank and get 40 fresh one-dollar bills.

- As you leave home in the morning, fold them and place them in your left pocket.

- Each time at work that you compulsively check your ?ngers you are to move a bill from your left to your right pocket.

I hear this from clients time and again: when they focus on scoring points, or avoiding a therapeutic consequence that we create together, they notice that they become less attentive to ?ghting the symptoms.

As you might imagine, these people are not easily persuaded to really want this experience. However, this is not the point of the exercise. The point is that they try to associate themselves to the task even if their initial attempts are clumsy. Clients can be encouraged to pretend to want their anxiety, like a role in acting class. This is a cognitive skill, so the work is directed to what they are mentally saying during practice. As they try to subvocalize as if they want to increase their doubt or discomfort, they will automatically dissociate from their typical negative interpretations.

If a client has trouble encouraging the physical symptoms, for example, “I can never want my hands to sweat,” then I suggest a minor shift in their focus. Instead of directly requesting physical symptoms to increase, I ask them to request that the anxiety disorder make the symptoms stronger. Instead of saying, “Come on! I really want to faint right now!,” they say, “please, anxiety, make me more dizzy.” This seems to be just enough misdirection and dissociation to make it tolerable to them, and accomplishes the same goal of competing with their resistance.

The central strategy of the game is for clients to want to embrace whatever the anxiety disorders want them to resist. One of the primary ways I convey the logic behind this wanting is by ?rst de?ning the process of habituation: prolonged exposure to a feared situation, bringing about a signi?cant decrease in fear.

Wanting Habituation

Habituation requires three elements: frequency, intensity and duration. You have to expose yourself to your feared situation often enough or you won’t progress. When you practice, you need to get up to a moderate level of distress. Practicing while you try to keep yourself calm actually slows your progress. Practicing between 45 to 90 minutes seems to be the ideal amount of time according to the research. These three components of habituation guide all homework assignments.I think there is a fourth element missing: the spirit of wanting to experience what you need to experience. Clients progress much more rapidly when they desire to have the habituation experience. Unless they are seeking and wanting frequency, intensity and duration as they go toward fear, then by default, they will be trying to do the opposite. They hope they don’t get anxious, that the symptoms don’t get very strong and distress doesn’t last very long. This makes no logical sense to me. If frequency, intensity and duration of exposure to distress and doubt are needed for me to get better, then I want to stumble upon a situation which stimulates my anxiety. I want to do that often, and I want my distress to last, and I want the sensations to be strong. These elements create habituation and habituation is my ticket out the door away from su?ering.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy does not teach this speci?c orientation to clients, although I think it should. If it did, it would alter clients’ disposition toward the problem, help to guide their practice, give them motivation and I’ll bet that it would alter neurochemistry as well. Analogously, if we are receiving chemotherapy for cancer treatment, it would be poor therapeutic form to go to each appointment dreading it, despite the fact that the side e?ects can truly be dreadful. Instead, you should see the chemotherapy as your friend, augmenting your body’s natural ability to heal. That’s good placebo.

The most important bene?t of applying the skill of wanting is that it speeds healing by truncating the habituation process. Clients learn rather quickly that if they invest in the stance of wanting, it returns to them the gift of a rapid reduction in their anxiety. They gain insight sooner in the process, after fewer practices and after fewer minutes within each practice. When they apply the skills of the game during practice, they actually have quite a hard time keeping their distress high (try as they might) or having it linger around for those 45 minutes. By paradoxically applying the orientation of wanting, clients have an “aha” experience during practice that brings freedom.

3) Master the skills of the game through applying technique and practicing (or being a "good student of the work")

I discuss with my clients the idea of “being a good student of the work.” Good students, of course, are clients who commit to following through on a homework assignment, and then work hard to keep their commitment.

One of Moira’s many OCD compulsions involved her needlepoint work. Frequently she felt compelled to tug on the thread ten times as she tightened a stitch. I o?ered her a new ritual to adopt. Each time she tugged more than once, on that next stitch she was to tug ten-plus-two times (12). The next stitch she had to subtract three to the number, tugging nine times. Ten on the next stitch, add two, and so forth, until she reached one tug. Her ten-tug stitch became a ritual involving 113 tugs in the next seventeen stitches. She hated that! But she did it, because she was a good student of the work. By forcing herself to stick with our little game, she increased her conscious awareness of her thoughts, feelings and urges during the moments just prior to her compulsive action. At the moment of the urge to pull more than once, she became alert to the punishing consequence. This strengthened her ability to turn away from it. Within a week, that compulsion was o? her list of troubles.

Skills Meet Challenge

Doubt relates to clients’ perception that their skills won’t match the challenges they face. If their assignment is within their skill level, then they will be more willing to go forward. This usually means we must lower the challenge and o?er them a performance goal within their perceived skill level.If I am an OCD checker, and I think I have just run someone over, I may yet have the skill to resist my urge to turn the car around and check the highway again. But how about pulling over and running around my car one time before I turn around? I can do that. And now I have interrupted the pattern, which provides me an opening for further changes. One day, as I am having the urge to check, remembering that I now must pull the car over and run around it (again), I might spontaneously decide that that is simply too much e?ort. At that point I will drive on, and thus experience, with little su?ering, exposure to my feared outcome without engaging in my ritual.

Score Points! Win Prizes!

The assigned tasks can be so challenging, so threatening to clients’ frame of reference that they refuse to practice. Even if they do practice, their early e?orts may give them only small gains. I mentioned earlier that I create a frame of reference of addressing anxiety as a game in which you can score points. For some clients I create prizes as extrinsic rewards in the early learning phase. Sometimes I o?er them metaphorical images, for example, “Imagine that if you walk all the way to the back of the store and stay there 10 minutes that I will magically transfer $10,000 into your savings account. Could you do it then? Play to win, as though your life depends upon it.”Currently, I have a large woven basket full of prizes, wrapped as gifts. In my anxiety group I bargain with clients: “Anyone who completes three practices this week can draw from the basket.” I have been hiding a $5 bill within two of the prizes as an extra incentive. Last month I rewarded the group member who earned the most points over the previous week with her choice among 12 new self-help books.

Recently I have generated a competition in the group during a several-week period. I agreed that for each member who practices at least 3 times I would contribute $5 into a weekly “pot” of money. I devised a point system to be used for every practice session. Each person decides where and how he or she will practice. Whoever scores the most points, wins the pot. The winnings can grow to be $90.

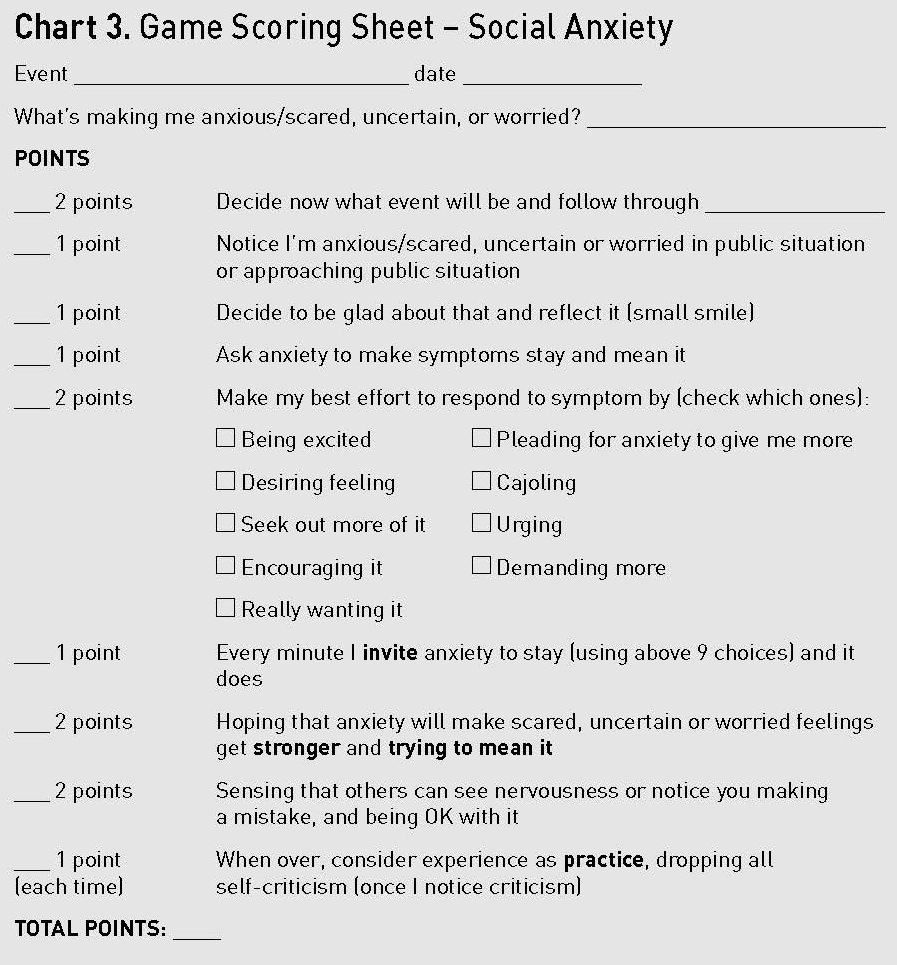

As you review Chart 3, you can see the essence of the provocative game and the weight of each type of activity. These illustrate the goals I want them to set during practice. They re?ect the essence of paradoxical action in fearful situations:

As you review Chart 3, you can see the essence of the provocative game and the weight of each type of activity. These illustrate the goals I want them to set during practice. They re?ect the essence of paradoxical action in fearful situations:In a threatening situation, step back and become an observer of your process, not be 100% the actor in the drama. Decide to be glad about having the doubt or distress. Put a little light smile on your face or in the back of your mind to re?ect it. Then, invite whatever struggle you are having, whether physical symptoms or worries, to stay. Work on trying to mean it. If possible, try to strengthen your move by intensifying your reaction. [For example, I o?er nine di?erent choices, such as the previously discussed demand that anxiety make the symptoms stronger.] No matter how strong the doubt and distress becomes, you should treat it as if it is never enough. Reward yourself for every minute you actively invite the symptoms to stay or to get stronger. Accept that other people might notice some problem you are having and for extra credit: hope that they do! Then, when you are done with the practice, learn to support yourself. Drop that critical, disappointed voice.

Creating the point system has a number of bene?ts. The client and I establish a broad strategy together that is manifested through speci?c actions during practice times. But they pick the practice times to apply the skills. They answer the question, “What can I do today to create some strong uncomfortable feelings for a while?” As they act on this choice, they are empowered and feel a sense of control. Once they are in the anxiety-provoking moment, the point system directly guides them to the therapeutic action.

It is poor strategy to get into a threatening situation and then decide how to act. In that setting, they are competing with a well-habituated set of instructions (“brace, worry, and avoid if necessary.”) Clients are much more likely to regress back to their safe actions, or inactions. When they understand the rules of the game and commit themselves to follow those rules, then recall them as they face threats, they have the best chance of winning.

Social Anxiety Strategies

Social anxiety disorder gives clients shaky hands, a quaking voice and worry about the critical judgments of others. Here is the role that it expects of the client: to not want the experience, to avoid it when possible, and to try to get rid of it. When choosing to play the game they ask for the opposite of what anxiety expects: they want anxiety to make their hands shake, their voice quake and their sense of threat heightened. Not only do they request those experiences, but they want them to stick around as long as possible! The clients then attempt to exaggerate their wanting of this experience, and might “desperately plead” for social anxiety to generate shaky hands, or to “cajole” the anxiety to make the experience stronger. They can increase their score by hoping that people will criticize their boring talk or question their shaky handwriting. Earn enough points, win a prize! They refuse to play the game that the anxiety disorder expects. They take charge and push that game board away and pull up their own game board of seeking out doubt and distress when anxiety wants them to defend or run.Julie

Julie decides to practice facing her social anxiety by eating lunch out alone. She walks onto the lunchtime crowd of “Moe’s Southwest Grill” and is instantly greeted by the cooks and other sta?. “Hello! Welcome to Moe’s!” they yell, and the other patrons turn to see who’s entered. Julie begins to feel the ?ush of red rise in her face as she smiles and nods her head in acknowledgement. Then inwardly she smiles and says to herself, “Yes! Another point.”Here she describes the process. I’ve added my comments in brackets to her key statements.

“I was really nervous walking in there. I felt like everybody noticed that I was by myself. But that was OK, because that was the point of the whole practice. [She is listening in to her inner conversation and she is permitting her feelings instead of blocking them.] Then having to ?nd a place to sit and making that conscious decision: Am I going to sit with my back facing everyone? Am I going to sit and actually have to look at everybody while they look at me? I made the choice to sit and look at everybody while they looked at me. [She is taking control of the situation by listening in on her process and choosing the more intimidating option.] ...I reminded myself that the longer I could stay and the longer I could be nervous and be OK with it, then the better it would be for me. [She has adopted a new belief system about her goals in the fearful situation: stay anxious to win.]

“I thought about how I could make it stronger. I thought that facing everyone while I ate would keep the anxiety going. I was just trying to think of ways to keep the anxiety going. [She is actively strategizing how to provoke symptoms as a powerful way to help her stop resisting.]

“I’m not as afraid of social anxiety as a word because I’ve taken social anxiety and I’ve turned it into a person instead of a condition. It’s not a mother, it’s not a father, it’s just this person or this entity and she wants me to take care of myself. She doesn’t want me to be embarrassed. When I do something that she thinks I could not do, she is impressed. I really like that because it is not a judgmental thing. It is like someone saying, ‘You really should wear a jacket, it’s going to rain.’ But you go out there without a jacket and it doesn’t rain, and they say ‘OK, you did it; you’re still a good person.’ So that’s how I’m thinking about it. [She now comprehends that those ogres, worry and anxiety, have been in her life to help her. They just do it in a clumsy way and she has found a better way. Julie will win this game for good.]”

OCD Strategies

OCD wants the person to try to get rid of any doubts about safety and to take any actions necessary to remove distress. Many OCD clients who fear contamination really do believe that at the moment of exposure they must repeatedly wash to save their life or the life of someone they love. Personifying OCD, I emphasize how it needs them to believe the speci?cs of their fears. Clients who win over OCD will hold fast to the belief that this is an anxiety disorder. As such, their battle should be with the physical symptoms of anxiety and the urge to end doubt. They should by no means battle with the content of the obsessions. It is never about germs or rabies or salmonella. It is always related to the fear of feeling distressed about threat. To play the OCD game clients set the overarching goal of seeking out doubt and distress.Eventually, everyone in OCD treatment will do exposure (of the feared stimulus) and ritual prevention, which is the standard treatment for this disorder. But modifying the ways clients obsess or how they perform the ritual is the most e?cient starting point for many. Starting with small, lower-threat changes allows clients to practice their new skills and experience early success. Instead of not washing their hands at all after they feel contaminated, clients can change how they wash, where they wash, or what they are doing mentally while they wash.

Jai

Jai was living in a residential program for teens. He struggled with about a dozen di?erent types of washing and cleaning rituals, especially when it was his turn to handle the after-meal cleanup. One ritual required that after he was ?nished with his (thorough) cleaning of the kitchen, he was to squeeze the sponge ten times while rinsing it under running water.In our ?rst treatment assignment I asked him if he would fool around with the ritual by switching hands each time he squeezed. In this case, Jai got to keep squeezing and keep counting. He simply altered hands, and switching hands was only a minor threat to him. This is what I call throwing the symptom cluster a bone. You leave in place major components of the ritual or obsession, thus lowering the threat level. However, it is still a change that begins to erode the original fortress of symptoms. He agreed to the assignment, and returned the next week to report how easy that task was. I then suggested this further revision: would he be willing to explore his ability to toss the sponge in the air and catch it with the other hand for each switch? Again, he agreed to this small, silly shift and returned the next week reporting no problems with the task. The following week, he simply squeezed one time and set the sponge down without struggle.

Jai’s playful approach to modifying his ritual became a relatively painless means to arrive at exposure and ritual prevention. It served as a building block for some of his more di?cult later encounters with OCD.

Jordan

Jordan, a physician, feared contamination with germs that might come in contact with her clothes during the workday at her medical practice. One of her primary rituals was to spray the entire front of her body with ammoniated Windex® as she left work. She used that same Windex® throughout her home when she felt threatened by germs. Ironically, while Jordan obsessed about becoming sick, her husband, who was also a physician in her practice, was developing serious respiratory problems from inhaling the ammonia. Over months, Jordan worked hard to tolerate switching the Windex® to vinegar-based, then to dilute it to a 50% solution and ?nally to a 33% solution. Each of these steps increased her doubt just enough that she could tolerate it and experiment with the change. Once she implemented the change, she incorporated it into her routine without much struggle.But we could progress no further with this or the other safety rituals she performed. Jordan was stuck on the content of her obsession: things had to be clean enough. I failed to persuade her that her attention actually needed to be focused on the strategy of confronting doubt and uncertainty.

Vann

Vann came into treatment struggling with OCD checking rituals that lasted up to ?ve hours a day. Often his concern was that he had missed seeing something he should have noticed: new scratches or dents on the trash can, dust particles under the telephone, an inappropriate item in the basement. Other times he checked as a way to prevent a disaster: an electrical cord will be wrapped around the trash can; his son will trip over some item on his bedroom ?oor; a ?re will start in the kitchen or a ?ood will occur in the basement. Some days Vann would check a particular item over a hundred times.Our ?rst ploys involved gently modifying his relationship with his symptoms. For instance, he would check the trash can, but only in slow motion, ever so gradually picking it up and unhurriedly rotating it in his vision. Or he would study the telephone, but not allow himself to touch it. These were his ?rst playful explorations into uncertainty and distress. By the sixth session we added a strategy of postponing. OCD would give him the impulse to check the basement immediately. He would choose to wait thirty minutes before he acted on that urge, again learning to tolerate his discomfort. Through this gradual exposure to the principles, by session nine he was able to avoid locking his house for ?ve days.

Here is how he described his progress by session 10:

“In the past I would pull out the backseat of the car, and if there were dirt there, I would have to clean it up. If a bolt was there I would look at it and get stuck on the backseat, focused on that bolt. Now I do this intentionally. I lift up the backseat and try to make something really bother me, try to feel anxious. I feel that anxiety, replace the backseat, shut the back door of the car and walk away.

When I ?rst started walking away I felt really anxious. I wanted to go back and look at something under that seat again. I felt as though I didn’t look at it hard enough and I’d want to look at it again. I would sweat a little bit, my heart would beat faster, I’d become very irritable and I felt very compulsive. I wanted to go check again! But I just decided I wasn’t going to do it. Sure enough, about two hours later the desire went away.”

Vann completed his treatment in eleven sessions over 5 1/2 months. In a follow-up twelve years later, he remained symptom-free and medication-free.

Conclusion

I began this conversation saying that when I work with anxious clients, I keep my points broad and simple and I focus on them repeatedly. My goal is to in?uence clients’ perspectives and shift their orientation. I encourage you to try the same.Help clients to turn away from the content of their fears whenever possible. You cannot always ignore content, because clients will be wrapped up in it. But get past content as soon as you can and move into the core themes of people with anxiety disorders: their struggle with doubt and distress.

The central strategy is for them to want to embrace whatever the anxiety disorders want them to resist. They have two choices. They can “stand down” by choosing to let go of their fearful attention and accept the reality of the current situation. This is the permissive approach. When they have completed treatment, this will be their most common response: to say, “I can handle this situation” and to allow their body and mind to become quieter. The other option is to choose to stay aroused on purpose and actually encourage anxiety to dish them more trouble. This provocative choice is an excellent option during treatment, because choice number one is so di?cult to embrace during early encounters. Conditioning and a set of false beliefs are calling the shots; they cannot simply relax on cue. Some treatment protocols will suggest that you help them expose themselves to the fearful stimulus and learn that they can tolerate it. I am suggesting that you put a twist on that set of instructions. Help them to take actions in the world that are opposite of what anxiety expects of them. Persuade them to go out into the world and seek out opportunities to get uncertain and anxious in their threatening arenas. This is a shift in attitude, not behavior. The behavioral practice is not to learn to tolerate doubt and distress, it is to reinforce the attitude of wanting them.

Our ultimate goal is to teach clients a simple therapeutic orientation that they can manifest in most fearful circumstances. Early in treatment, however, you will also need to provide a speci?c system to follow, with simple rules that guide their interactions with fearful anxiety. Using behavioral practice, encourage them to repeat this new interaction again and again, in all their fearful situations.

You can assume that one of the biggest obstacles to success will be poor planning just moments before the encounter. Whenever they wait until they are scared before deciding the best course of action, then conditioning and faulty beliefs will dictate that they struggle or avoid. In that setting, they are trained by fear to mindlessly seek safety and comfort. Before they enter any situation that is potentially threatening, they should review their objectives and remind themselves of their intended responses.

Thinking of their relationship with anxiety as a mental game o?ers both a broad therapeutic point of reference and speci?c actions that manifest it. Initially, your skills of persuasion and their belief in you will push them to challenge their faulty beliefs. After that, experience will be their greatest teacher. Once they have acted on these beliefs and gotten feedback during the fear-inducing event, that learning will put the power in their new orientation and it will be self-sustaining. They will then have a set of instructions, such as “anxiety, please give me more” or “I’m looking for opportunities to get distressed” that will point them toward simple choices during di?cult times. And they will have a skill set (that I laid out in Charts 2 and 3) that they believe will match the challenge of the situation.

Copyright © 2006. Psychotherapy in Australia. Reprinted with permission.

CE points are a great way to save if you need multiple CEUs. Get up to 45% discount when you buy packages of 10, 20 or 40 points. Your CE points will be redeemed automatically at checkout. Get CE packages here.

*Not approved for CE by Association of Social Work Boards (ASWB)

- Describe the cognitive-behavioral underpinnings of Wilson's work

- Apply key strategic and paradoxical interventions with anxious clients

- List commonalities among anxiety disorder treatments

R. Reid Wilson, PhD is a licensed psychologist who directs the Anxiety Disorders Treatment Center in Chapel Hill and Durham, North Carolina. He is also Clinical Associate Professor of Psychiatry at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine. Wilson specializes in the treatment of anxiety disorders and is the author of Don’t Panic: Taking Control of Anxiety Attacks (Harper Perennial, 1996), Facing Panic: Self-Help for People with Panic Attacks (Anxiety Disorders Association of America, 2003), and is co-author with Edna Foa of Stop Obsessing! How to Overcome Your Obsessions and Compulsions (Bantam, 2001). Wilson served on the Board of Directors of the Anxiety Disorders Association of America for twelve years and was Program Chair of the National Conferences on Anxiety Disorders from 1988-1991. In 2014 The Anxiety and Depression Association of America honored Wilson for a lifetime of service in treating anxiety disorders, awarding him the Jerilyn Ross Clinician Advocate Award at its annual conference in Chicago.

R. Reid Wilson, PhD is a licensed psychologist who directs the Anxiety Disorders Treatment Center in Chapel Hill and Durham, North Carolina. He is also Clinical Associate Professor of Psychiatry at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine. Wilson specializes in the treatment of anxiety disorders and is the author of Don’t Panic: Taking Control of Anxiety Attacks (Harper Perennial, 1996), Facing Panic: Self-Help for People with Panic Attacks (Anxiety Disorders Association of America, 2003), and is co-author with Edna Foa of Stop Obsessing! How to Overcome Your Obsessions and Compulsions (Bantam, 2001). Wilson served on the Board of Directors of the Anxiety Disorders Association of America for twelve years and was Program Chair of the National Conferences on Anxiety Disorders from 1988-1991. In 2014 The Anxiety and Depression Association of America honored Wilson for a lifetime of service in treating anxiety disorders, awarding him the Jerilyn Ross Clinician Advocate Award at its annual conference in Chicago.See all Reid Wilson videos.

Reid Wilson was compensated for his/her/their contribution. None of his/her/their books or additional offerings are required for any of the Psychotherapy.net content. Should such materials be references, it is as an additional resource.

Psychotherapy.net defines ineligible companies as those whose primary business is producing, marketing, selling, re-selling, or distributing healthcare products used by or on patients. There is no minimum financial threshold; individuals must disclose all financial relationships, regardless of the amount, with ineligible companies. We ask that all contributors disclose any and all financial relationships they have with any ineligible companies whether the individual views them as relevant to the education or not.

Additionally, there is no commercial support for this activity. None of the planners or any employee at Psychotherapy.net who has worked on this educational activity has relevant financial relationship(s) to disclose with ineligible companies.

CE credits: 2

Learning Objectives:

- Describe the cognitive-behavioral underpinnings of Wilson's work

- Apply key strategic and paradoxical interventions with anxious clients

- List commonalities among anxiety disorder treatments

Articles are not approved by Association of Social Work Boards (ASWB) for CE. See complete list of CE approvals here

Psychotherapy.net offers trainings for cost but has no financial or other relationships to disclose.