Need Help?

Email or Call: 1-800-577-4762

Email or Call: 1-800-577-4762

Sign up for our

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

Need Help?

CONTACT US

CONTACT US

Couch Fiction

Filed Under: Beginning Therapists, Humor

In This Article…

Couch Fiction

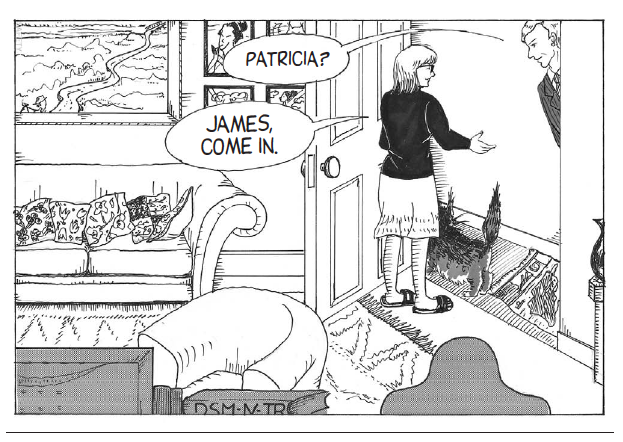

This is an excerpt of a beautifully illustrated graphic novel based on a case study of Pat (a sandal-wearing, cat-loving psychotherapist) and her new client James (an ambitious barrister with a potentially harmful habit he can't stop). The succinct footnotes offer a witty and thought-provoking exploration of the therapeutic journey. If you are curious of how Pat and James carry on this therapy, you can buy the book here .

Nobody's Perfect

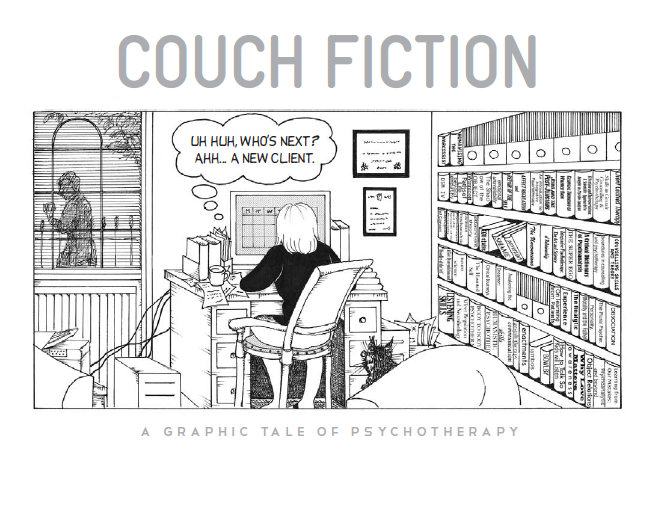

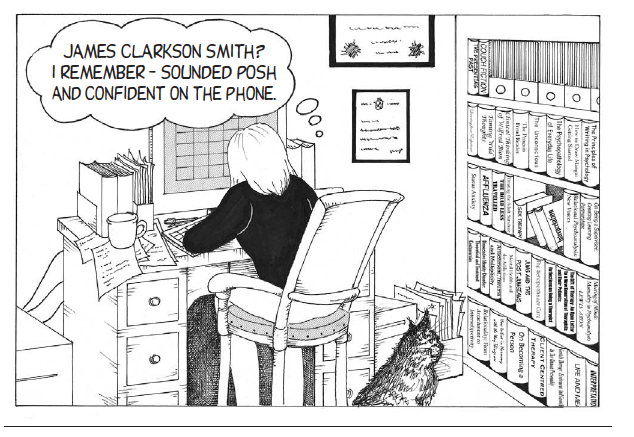

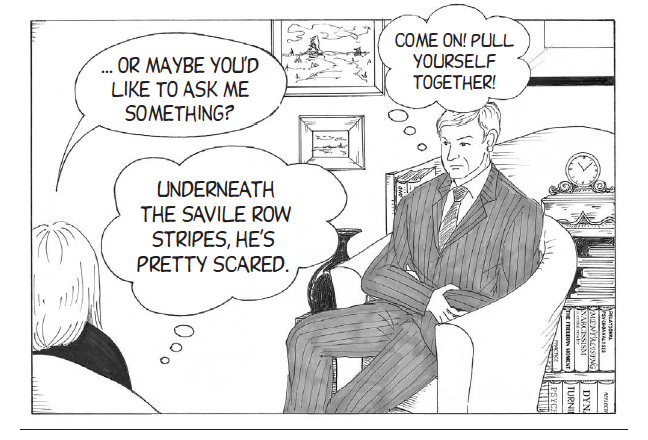

Some schools of psychotherapy suggest that prior to a session, a therapist should empty themselves of preconceptions in order to maintain the openness of mind necessary to be aware of the nuances of the encounter. The psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion said that the therapist must prioritise perception and attention over memory and knowledge as the practitioner’s most basic working orientation. This position is almost always adhered to by the most experienced therapists (occasionally due to dementia rather than a rigid adherence to theory). The therapist in this story is not rigidly adhering to this theory. She is not a perfect therapist and there is no such thing.

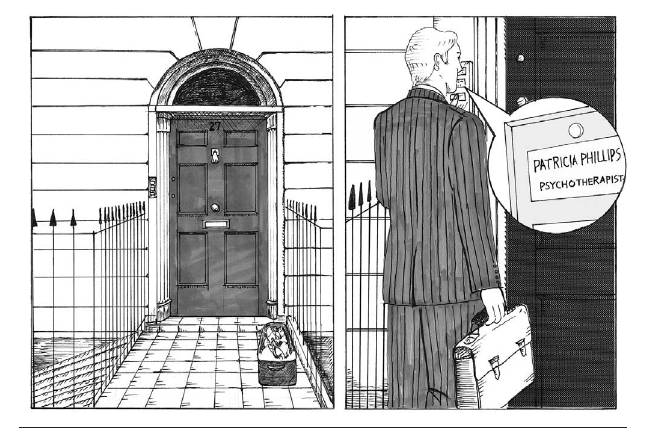

I wonder how much research has been done on the impact of recycling bins and their contents on the doorsteps of therapists’ premises? I would be especially interested to know of their impact on the first-time client.

Many psychotherapists do not worry about the impression that their appearance makes on their clients*; some have a habit of wearing open-toed orthopaedic sandals whatever the weather. Footwear can give an idea of whether a therapist is working from home or renting a room – slippers or open-toed sandals in winter are a sure sign they are home based. *This is either because they have worked through their own narcissism issues or they are inherently unstylish, or both.

Truth

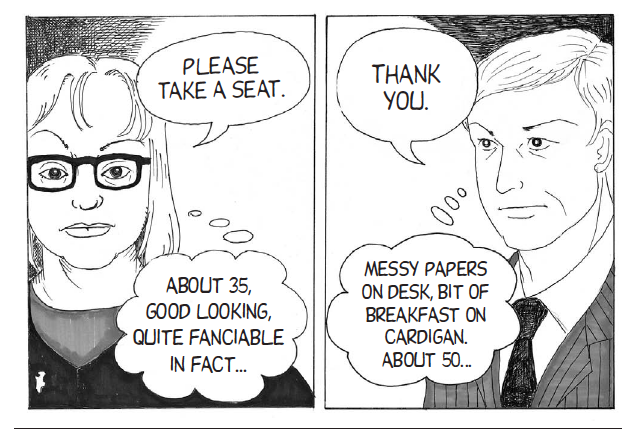

We can never assume that the absolute truth in and of another person can ever be completely known. It is, however, important in psychotherapy to strive for that truth. Whether Pat clocking that she finds James attractive can be seen as striving for absolute truth is debatable.

In the past, unlike Pat, many therapists didn’t ask questions in order to be a blank screen onto which the client then projects. Projection is when instead of having pure contact with another, we project a part of ourselves onto the other person and relate to our own projected part, rather than, or as well as, to the person before us. It is now recognised that a practitioner who says nothing is anything but blank and, however talkative or silent she is, the client will still react to her as she is in the present (with her funny sandals and her recycling). Nor will failing to remain silent prevent projection or transference. Transference is when we make subconscious assumptions about the person before us in the present, based on our experience of people we have known in the past. For the record, countertransference is what therapists call the feelings that the client causes to emerge in the therapist. It is desirable that therapists recognise their countertransference so as not to complicate an already complicated matter.

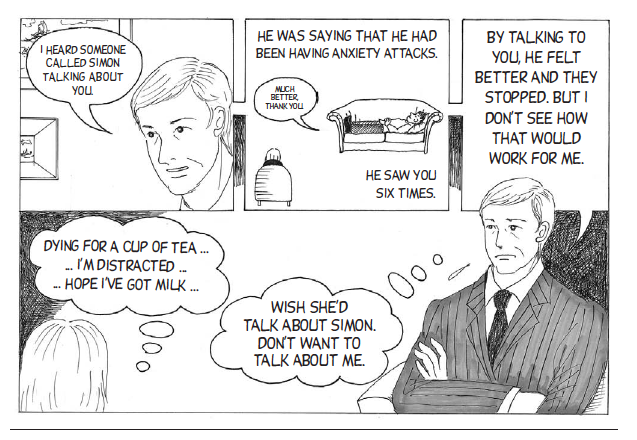

By talking about Simon, James is avoiding the subject it would better serve him to talk about – himself. Pat appears to be experiencing a countertransferential parallel process to James, as she too is finding it hard staying with the business in hand. Possibly, due her distraction, Pat has missed the clue that James ‘heard’ Simon talking about her, rather than James reporting having a conversation he had with Simon. It is as though he has taken the information from Simon by stealth. She missed this. It does not matter. If it is important that a behavioural pattern is addressed, the client will invariably either demonstrate it again, or bring it up later on.

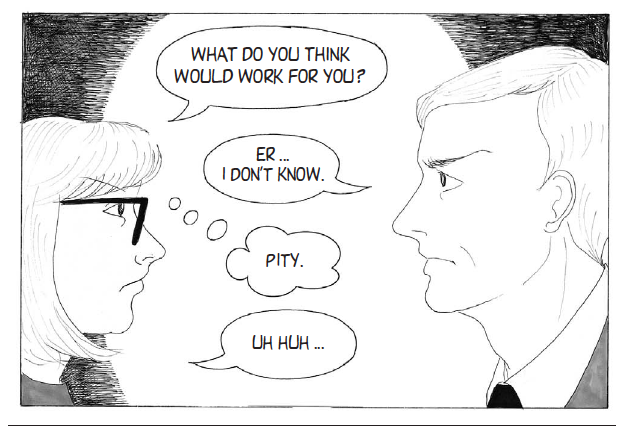

Research has shown that clients are most likely to make positive changes in therapy when the therapist uses the client’s own theory of change, or when the therapist’s own ideas about change coincide with the client’s previously held psychic beliefs. This is why Pat asks James what would work for him.

Success

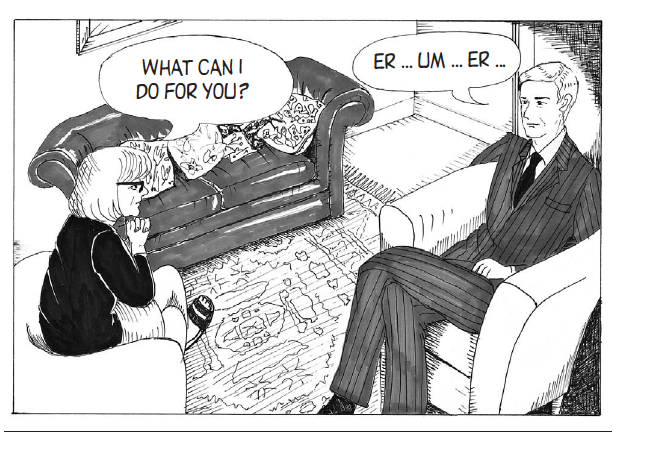

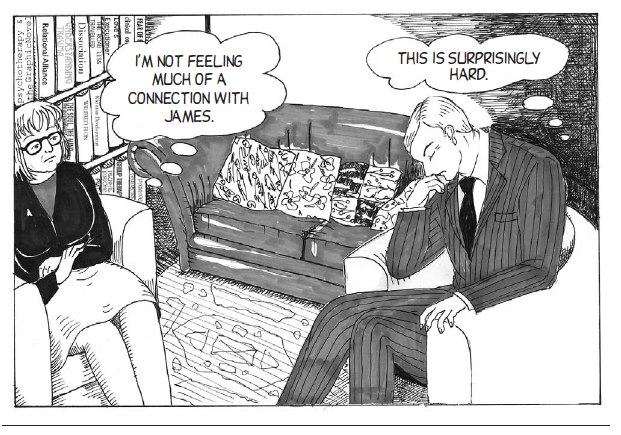

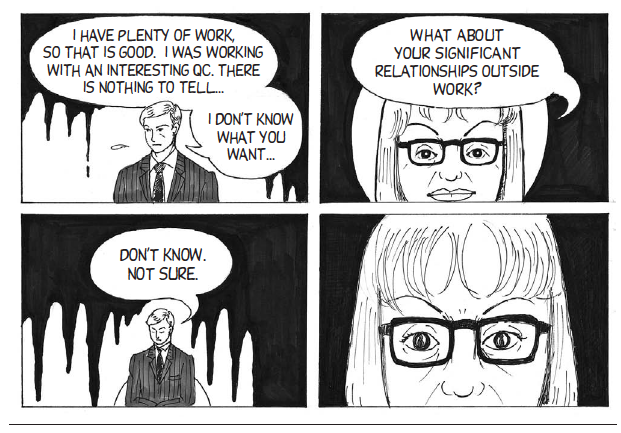

The highest indicator for a successful outcome for therapy is the client’s expectations, motivation and hope. The second is the relationship between the client and the therapist. Neither area seems to be thriving for Pat and James at this stage in the therapy.

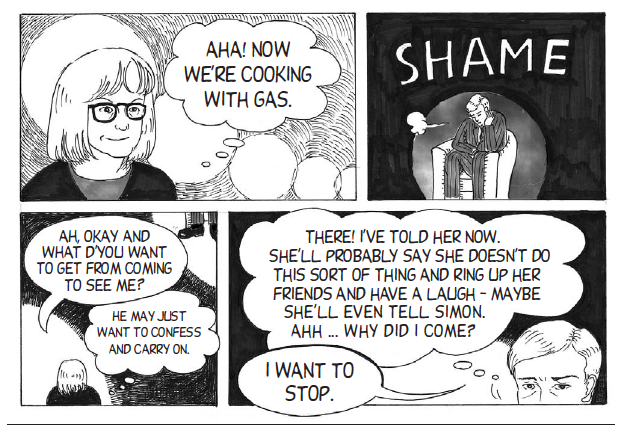

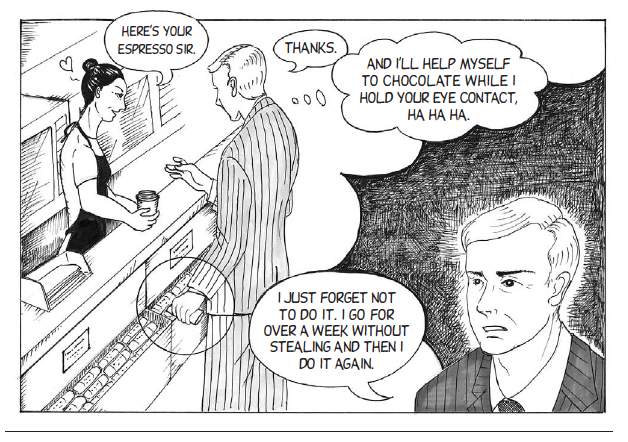

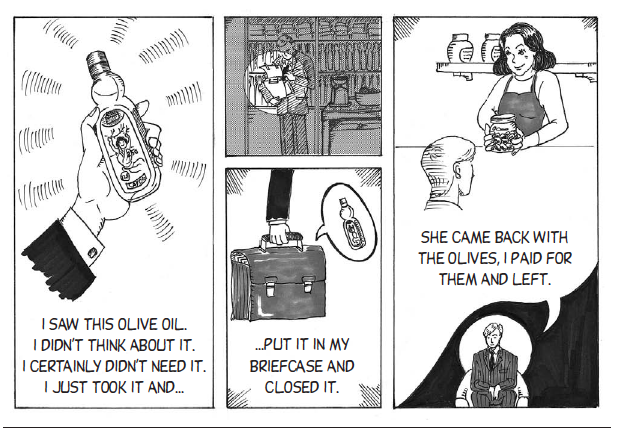

Many clients report that naming the issue that brings them to therapy out loud for the first time can be a powerful experience, even overwhelming.

Psychotherapists are often asked whether it is boring listening to people talk about themselves all day long. The answer is no, not when they are really talking about themselves. If the therapist does feel bored, she will be interested in that feeling because it will be telling her what needs to be addressed in the session is probably not being attended to. Therapy can break down if client and therapist have not agreed goals. By asking James what he wants, Pat is beginning to negotiate a potential contract for their work together. She is also checking out whether she would be willing to work with James. Not many therapists want to act just as a confessor.

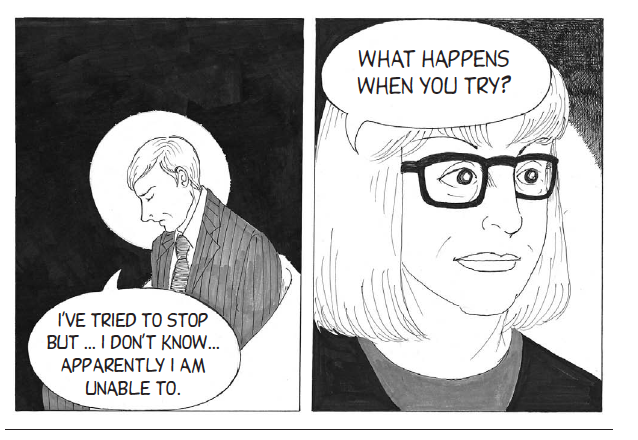

Many people consider undergoing therapy only as a last resort. They have usually tried various strategies to change or to feel better before getting help. Pat would not want to suggest something James has already tried, hence her line of enquiry.

Although kleptomania isn’t a particularly common compulsion amongst people in a position to afford private psychotherapy, it is not unusual in that most of us continue with a habit we would rather we didn’t. For example: procrastination, smoking, eating too much, being over critical, over-reacting, acting shy, getting drunk… the list goes on.

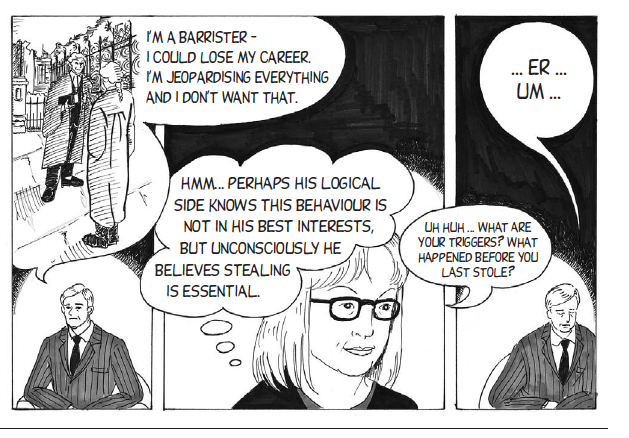

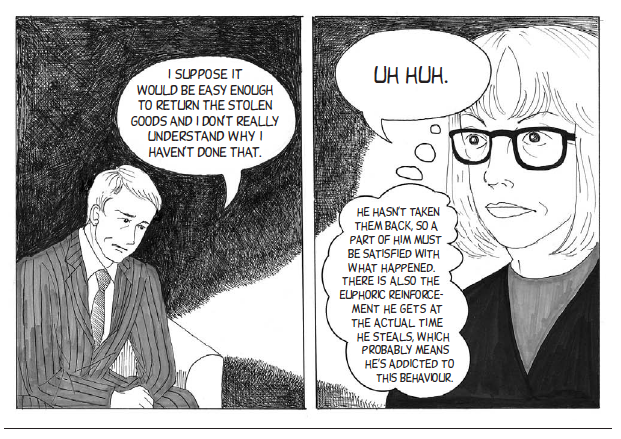

Inevitably when a therapist looks back over a session, there is always something she could have done more sensitively or intelligently. Here, Pat is going too fast for James in looking for triggers for his behaviour. It would serve him better at this stage if she empathised with him more. The idea, though, is not to be perfect. The idea is to remain authentic while striving for the unknowable truth.

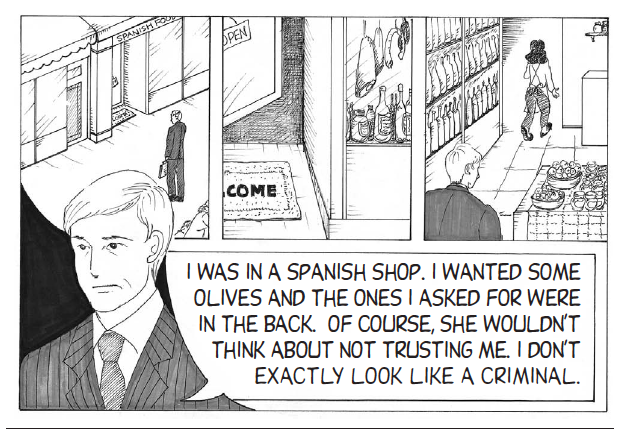

If this was an ordinary conversation and not a therapy session, Pat would probably go into raptures about the combination of pitted black olives in chilli oil with pickled garlic available at the nearby Spanish deli. But this isn’t an ordinary conversation and so she does not share her passion about olives with James. Although James is relating a story about buying olives, olives are obviously not the subject here.

The process of telling the story and the relationship of the teller to the story is of more interest to a therapist than the content of the story itself. The content is the icing but the process is the cake itself. This is why therapists will often ask a client how they feel about the story they’ve just told. It is another of the differences between a normal conversation and a therapy session.

Pat is formulating theories about James’ behaviour that she is choosing not to share. Therapists commonly refer to this process as ‘bracketing’. Pat does not know James very well yet, so she is unsure about what he can and cannot tolerate hearing at this stage. Possibly it would serve James better if she also bracketed her line of enquiry about triggers, as her inability to let go of the trigger theme is in danger of rupturing their relationship. Bracketing is more complex than just withholding information. It actually means suspending judgment. To understand this thoroughly one has to study the philosophy of Husserl. He talked a lot about how seeing a horse qualifies as a horsiness experience irrespective of whether the horse appears in reality, in a dream or hallucination. He also talked about the very essence of how you experience the phenomenon of horse essence, but I’ll bracket that.

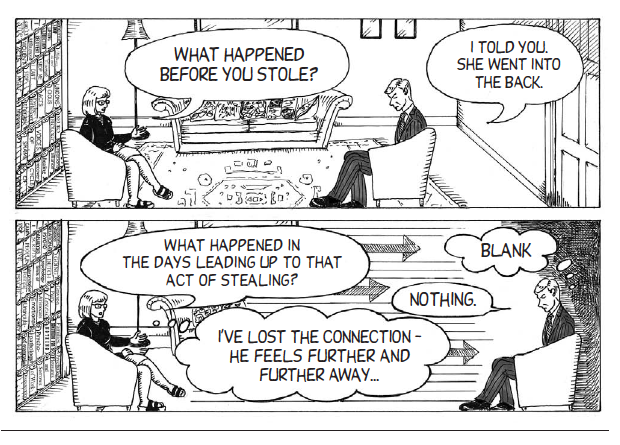

Pat continues to pursue her trigger theory. Her speed here means that she doesn’t stay in contact with James. In her enthusiasm, she appears to have forgotten her early counselling training on closely tracking the client and going at the client’s pace. James is being pushed not only to where he does not want to go, but where his body is unwilling to go, and so he goes blank. Going blank, or dissociating, is not an act of will but an automatic response to certain stimuli. Some people are more prone to this response than others, especially if they started to do it at a very young age. You might assume – and perhaps this is Pat’s mistake – that James being a highly educated professional person would be able to follow Pat’s simple questioning. But all of us have the potential to be highly functioning in some areas and relatively immature in others.

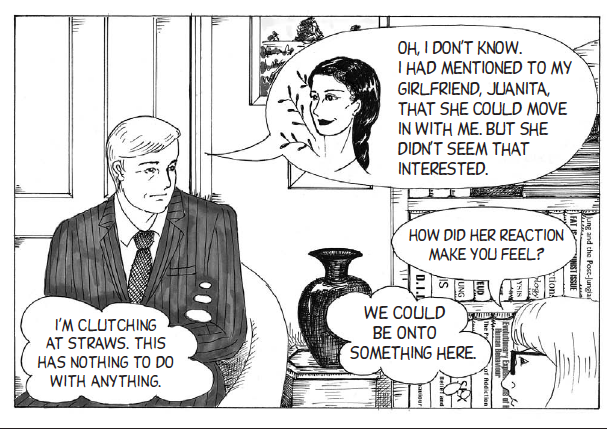

In most people’s lives, there are three main areas: what we do, where we live and who we live with. Pat has tried the first area, what we do – work, in other words – and did not come up with anything. She’s moved on to the people in his life to see if anything untoward is happening there.

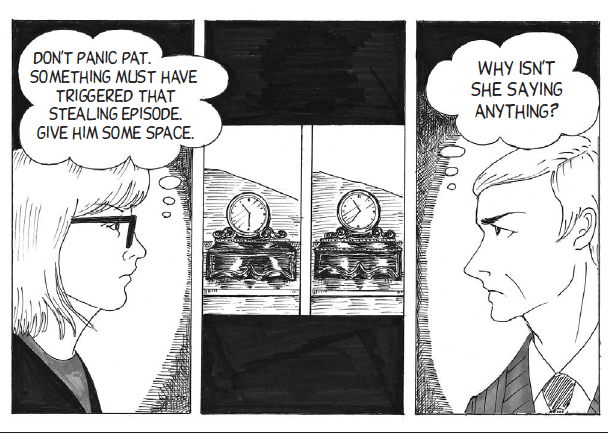

Therapy is not like a normal conversation in that there can be long silences in order to give things time to emerge from the unconscious mind into awareness. Although unless this has been previously negotiated between the parties, what is likely to come up is,‘Why isn’t she saying anything?’ or ‘What am I supposed to do now?’

As either a client or a therapist, if something pops into your mind, it may be worth sharing. Even if, on your own, you cannot see its relevance.

If you are eager to know the end of the adventures of Pat and James, you can purchase Couch Fiction here and benefit from a 25% discount on this and all other psychology books from Palgrave Mcmillan. Please click here, select the book of your choice, and enter promocode PSYCH2011 at checkout.

Text and Story © Philippa Perry, 2010 Illustrations © Junko Graat, 2010

Philippa Perry is a psychotherapist, psychotherapy supervisor and a fine art graduate. She wrote the story in Couch Fiction.

Junko Graat trained and worked as a product designer in Japan before coming to England. She is a student of philosophy and practices as an illustrator. She is responsible for the art in Couch Fiction.

Philippa Perry and Junko Graat was compensated for his/her/their contribution. None of his/her/their books or additional offerings are required for any of the Psychotherapy.net content. Should such materials be references, it is as an additional resource.

Psychotherapy.net defines ineligible companies as those whose primary business is producing, marketing, selling, re-selling, or distributing healthcare products used by or on patients. There is no minimum financial threshold; individuals must disclose all financial relationships, regardless of the amount, with ineligible companies. We ask that all contributors disclose any and all financial relationships they have with any ineligible companies whether the individual views them as relevant to the education or not.

Additionally, there is no commercial support for this activity. None of the planners or any employee at Psychotherapy.net who has worked on this educational activity has relevant financial relationship(s) to disclose with ineligible companies.

Junko Graat trained and worked as a product designer in Japan before coming to England. She is a student of philosophy and practices as an illustrator. She is responsible for the art in Couch Fiction.

Philippa Perry and Junko Graat was compensated for his/her/their contribution. None of his/her/their books or additional offerings are required for any of the Psychotherapy.net content. Should such materials be references, it is as an additional resource.

Psychotherapy.net defines ineligible companies as those whose primary business is producing, marketing, selling, re-selling, or distributing healthcare products used by or on patients. There is no minimum financial threshold; individuals must disclose all financial relationships, regardless of the amount, with ineligible companies. We ask that all contributors disclose any and all financial relationships they have with any ineligible companies whether the individual views them as relevant to the education or not.

Additionally, there is no commercial support for this activity. None of the planners or any employee at Psychotherapy.net who has worked on this educational activity has relevant financial relationship(s) to disclose with ineligible companies.