Email or Call: 1-800-577-4762

NEWSLETTER

CONTACT US

The Bad and Good Ghosts: A Story of Reauthoring in Narrative Therapy with Children

“There’s a boy, there’s a kid always living in my heart every time the adult shivers he comes and gives me his hand.” Brant and Nascimento [1]

My childhood has been a never-ending playground of theoretical and practical knowledge that has influenced my own evolution as a therapist working with children. In my work with children, I bring my own valuable child-within who leads me through the paths and crossroads of therapeutic work and inspires my imagination and curiosity toward a world to be discovered. Favored by being born into a family where other children arrived year after year, older siblings like me were taught to take care of the younger ones. I was privileged to be raised in a generation where neighborhoods were populated with children and playing in open spaces was imperative. Thus, in my consultations, echoing the lines of Brazilian composer and musician mentioned above, there is a child always living in my heart.

This article was produced because I felt invited to share a reflection on everyday clinical practice, understanding it as a written dialogue between me, the author, and other authors or readers. It involves the work I did with a family consisting of parents and two children ages eight and four. The consultations were mostly made involving the mother and her eldest son, whose main issue was the indomitable spirit that appeared whenever he was contradicted by her, with an abundant flow of anger, accusations, and dissatisfactions arising on his part and paralyzing her. These are therapeutic conversations that took place during the year 2020 and were crossed by the COVID-19 pandemic, which brings as a challenge the development of resources to maintain the therapeutic process.

In the dialogue with the reader, I intend to report fragments of the practice, seeking to give visibility to: 1) externalizing conversations as a ludic dialogical resource and promoter of preferable changes, 2) the production of therapeutic documents in the format of therapeutic chronicles (1, 2), a useful resource for pointing out remarkable moments in the participants’ reauthoring process, and 3) to the share of moments in which the use of online technology helped the co-construction of generative therapeutic relationships, making it possible to move forward in the conversational process.

Chatting with Some Textual Friends Before Entering the Therapy Room

Michael White (3), despite the expressive systematization capacity of his work as a whole, privileged the developments of his practice so that the spirit of narrative therapy could be expanded, without letting it be tied down by any preponderant discourse of this or that therapeutic school. David Epston, echoing this plurality of meanings in narrative therapy, points out both the irreverence, improvisation, and imagination present at the center of everyday life and the indignation with the injustice that generates human suffering (4). Thus, narrative therapy actively questions the individual centralization of human problems and invites one to think about their insertion into the dominant social discourses that configure people’s lives.As a therapeutic stance, this questioning promotes an egalitarian relationship between therapist and client and denies norms that subject people to standards on how they should be, feel, and act. Such a decentered position of the therapist facilitates a joint construction of choices that clients wish to assume about their problems and difficulties, based on the values and beliefs that guide their lives. Thus, change is built from new shared meanings toward the dissolution of the problem (5).

To face the dominant stories that produce this deficit and limited identity construction, the externalization of the problem — later renamed externalizing conversations — was an ethical and creative response developed by Michael White (3,6,7) to counter the power of uniform descriptions about people, which engulfs all the uniqueness that each individual has in facing their difficulties. Such conversations, as a dialogical resource, invite participants to understand that the problem is the problem and not the person; an approach that encourages people to question the oppression that problems acquire over them, as well as to weave the reauthoring of their lives. Michael White says:

There is a sense in which I regard the practice of externalizing to be a faithful friend. Over many years, this practice has assisted me to find ways forward with people who are in situations that were considered hopeless. In these situations, externalizing conversations have opened many possibilities for people to redefine their identities, to experience their lives anew, and to pursue what is precious to them.

This fascinating spirit that rests on what is unique in each person and is so present in working with children is reflected in the enthusiasm of another young client: “I said to my father: ‘There must be some magic here! That cry that I used for everything disappeared!’”

With the inspiration of “as if it were magic,” I will present below the report of the family care on which this article was based. The meetings were mostly attended by the mother (Aurora) and her eldest son (Daniel) since the difficulties described brought many misunderstandings and a feeling of hopelessness in the relationship between them. Since problems organize the system, Leo, the youngest brother, was included when conflicts between children intensified with the social isolation imposed by the pandemic; the father could participate in only a few sessions, when we managed to schedule appointments after his work shift. In these meetings, where the whole family got together, playing freely was the main objective (8).

A Cry for Help

Even in the first days of the January 2020 holidays, Aurora, the young mother of Daniel (eight years old) and Leo (four years old), was very distressed at not achieving a balanced relationship with her eldest son, who “throws himself at the television” and does not commit to his obligations, from taking care of personal hygiene to school obligations during class time. Born at 7 months of pregnancy, he was assessed during the literacy period and received a diagnosis of Attention-Deficit Disorder (ADD), in addition to living with an uncomfortable dysgraphia and psychomotor immaturity, which forced his mother to follow up on school tasks, correct spelling, and “correct the ugly handwriting.” Always complaining, he got irritated when his mother pressured him: he screamed, cried, and accused her of being a bad mother. It left her “out of her mind,” since she did the best she could. In those moments, anger also dominated her, from which words emerged that she would never have used if she could think before speaking. She therefore felt very guilty and convinced herself that she really wasn’t a good mother.The family had moved to the city of the maternal grandparents two years before, in the hopes of receiving family support for the care and treatment of their children. They left behind schools, relationships, friendships, leisure, and professional stability. They faced professional and financial obstacles and the expected help from their family members did not materialize. The couple underwent a reorganization of their responsibilities as family providers, with the children’s father expanding his professional activities, while Aurora saw hers reduced due to the care and education of her children. Thus began a lasting period of frustration, overwhelm, and exhaustion.

“Hello, May I Come In?”: Expanding the Meaning of the Problem

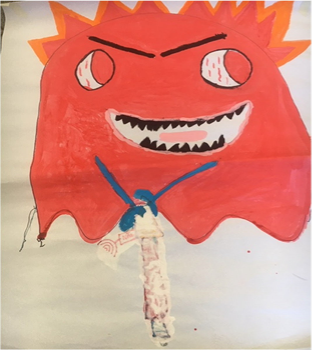

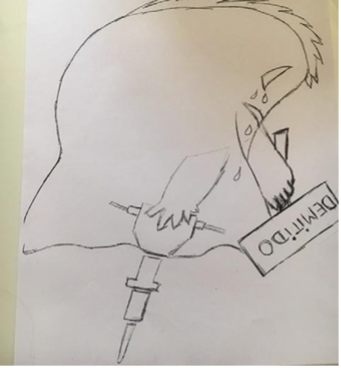

Aurora and Daniel attended the first meeting. Daniel was a silent and observant boy apparently uninterested in participating in the conversation that concerned his failures in everyday life. Aurora spoke about all her disappointments with her son, such as: watching too much television, complaining about everything although she was always helping him, lacking autonomy for schoolwork, avoiding physical activities, and being uncooperative and disobedient to his parents’ expectations. His greatest difficulty, however, concerned the inability to control himself before exploding into fits of rage when contradicted. Uncomfortable, Daniel silent and sad, slowly walked away and disappeared from the room. Another environment was more interesting to him: the playroom.While planning what could be drawn, a different conversation took place. New vocabularies sprouted from a much more collaborative mother-son relationship: “Is it a monster or a ghost? It’s quite big, so it needs a larger paper. It has a skirt, and many teeth in the mouth; the hair is spiked.” Daniel started to see the image of the problem: “Mom, the monster will be red, because red is the color of anger.” The boy, encouraged by the change of direction of the conversation, busied himself in coloring with care and the mother patiently accompanied him in the dance of the brushes. By photographing with paints and brushstrokes, the problem takes on form: “Wow! It’s nice! Mom, you look mean!”

Ghost of Fury

Satisfied with the reproduction, Daniel says: “It is a giant of Fury that torments a lot, attacks the head, and keeps hitting it.” The part of the conversation below illustrates the dialogue that is being woven around the externalized problem (the acronyms T, D, and A, refer respectively to Therapist, Daniel, and Aurora):

T: I think he has a jackhammer in his hands and drills holes in your head to get in! (I paint a tool in the hands of the giant). Could we come up with something to let you know when he’s turning on the jackhammer? (I paint a radar that says “No,” when it notices that the giant is approaching).

D: No... it crosses your mind... It’s a ghost.

T: Oh! We are getting to know him better! He looked like a giant, but he’s a ghost!

D: Yeah, he doesn’t drill holes; it goes through the head (erases jackhammer drawing with white paint).

The separation between the person’s identity and that of the problem does not exempt them from facing the damage that this has brought to their lives. According to Michael White, it enables them to assume this responsibility, and, in this way, they are encouraged to establish a more clearly defined relationship, in which a range of alternative possibilities becomes possible. And continuing...

T: And does he take advantage of some “little windows” to get inside your head?

A: I think it’s when he gets jealous of his brother and when we go against him.

An alternative way of talking about the difficulties that permeate family relationships is under construction without, however, pointing out the child’s deficits, and blaming him. Externalizing conversations, by objectifying the problem, offers an antidote to internal and essential understandings of an individual.

Building an Identity for the Problem

The problem, now named Ghost of Fury, is gradually discovered through a curious investigation where I learn from the clients about their experience. The Ghost of Fury is 1,000 years old and lives in every child’s house for one year. It arrived when the family moved from the city where they lived two years ago, leaving the loving paternal grandparents. He feeds on people’s anger and his favorite food is “rage burger.” He lives in hell and other evil ghosts also live there.Upon hearing Daniel’s vibrant description, Aurora reported that the parents and children lost their friends. The children separated from their schoolmates, from the playground in the old house, and from the paternal grandparents’ beach house. She says: “Daniel always says it was my fault we moved here. He doesn't like it here.”

D: Yeah, we had to come here because she got a job here…(notices the mother’s tears) Mom, are you crying??!!!!

T: I think you were all very sad to have moved to another city. Nothing happened as you expected...

A: He says I'm not a good mother, I feel very guilty. I do everything for them, I can hardly even work…

T: Yeah... one of these evil ghosts’ tricks is to make mothers feel guilty. They disrupt the whole family’s life.

D: Not my father’s life! He works and comes home late and just sits on the couch watching TV, right mom? (Aurora laughs).

Looking for the influence that the problem has on the life of Daniel and his family, I highlight the following excerpt:

T: What does he want for your life?

D: That I become evil? He wants me to be mean!!! (His eyes are wide open, pointed at his mother).

It is important to note here the change in the child’s expression that seems to reflect on the influence the problem has on his life and suddenly discovering his real purpose. And continuing:

T: And what does he want for your family?

D: He wants us to fight, stay in front of the TV alone, without talking to our mother, without playing... He doesn’t just disturb the family; he also goes to my (maternal) grandparents’ house. The most nervous is my grandfather. He drives my grandfather crazy.

D: Mom, grandpa needs to come here too!

Michael White says that this type of conversation, through influencing questions, compares to investigative journalism and its first objective is “to develop an exposition of the corruption associated with abuses of power and privileges,” imposed by the problem. Like investigative journalists, therapists are not involved in the domains of problem-solving or engaging in conflict, but, again referring to White, “Rather, their actions usually reflect a relatively ‘cool’ engagement.” In contrast, clients also assume an investigative reporter position, reflect on their experience, and contribute to exposing the character of the problem. They denounce its objectives, purposes, and activities.

A Story About the Externalized Problem Inspired by the Idea of Poetic Documentation

For White and Epston, the written word is an ideal path for discoveries made during therapy which, like documents, can be evoked, read, and recreated. Written tradition, through “making visible,” highlights extraordinary events, giving prestige to an alternative narrative (9). Still, according to Campillo Rodriguez (1), writing as a therapeutic resource opens up many paths through which people can see themselves through the eyes of the other.During clinical consultations, therapeutic poems build, in a special way, an opening to new stories, which play with the imagination and give clients the freedom to experience their own images, sensations, and new meanings.

Discussing the usefulness of therapeutic poems in her work, Sanni Paljakka (2) writes:

Due to their unusual form (the lack of requirement for the shiny completeness of sentences and ideas in prose text), these poems have opened up a unique way for me to play with ideas. Writing in poetry form allows me to pit the horrors and hauntings of a problem story against a confection of possible counter-story ideas with no regard to orderly sequencing of life experiences or the flow of a therapy conversation.

So, at the opening of the session following the revelation of the Ghost of Fury, I asked Daniel and his mother to sit down comfortably and listen to a text that I wanted to present to them (Although the authors point out that poetic documents should be written exclusively with the words expressed by the client, I took this therapeutic tool as an inspiration, adding a personal way of narrating, to what I preferred to name therapeutic chronicles.):

It was a problem and it was a gigantic

A giant that was so gigantic, it tormented everyone

It tormented the boy even more

The boy was a child

And he did the worst for the child Just for the kid, he had a jackhammer

He made little holes

In the boy’s head

When he was a child and the boy was a child

Clever

Thoughtful

Observer

And the boy had an artist mother

The child boy had an artist mother!!!

The smart boy and the artist mother took a picture of the giant

Click, Click, Click

Red he was

With funny hair and there was the jackhammer Making holes in the head

And making everyone nervous and quarrelsome and then... Sad

And found out the giant was all Rage Aha!!!

Now we know you!!!

And the smart boy and the artist mother didn’t notice...

The Giant of Rage, that was his name, was very intelligent

In a brush step, zas!!!

Changed to Ghost of Fury

What the hell!!!

Ghosts don't need little holes to get into the heads and families of smart boys and nice moms

Ghosts walk through walls

The smart boy figured out the trick. He found that the ghost goes through his head

And lo and behold! He knows many tricks to do bad things

He is 1,000 years old.

I recited the chronicle, dramatizing it in such a way that the emphasis fell on the resources and extraordinary events subjugated by the problem (the boy was a child; he was smart, thoughtful and observant; the child had an artist mother; the smart boy and the mother artist took a picture of the giant), as well as the perverse purposes fueled by the problem (the giant that especially affects the boy, who is a child; his evils are preferably directed at him; a very intelligent giant, who magically transforms into a ghost to cross heads).

It was surprising to her to be perceived as an artist and she reported other craft skills, inherited from her mother. Daniel praised his maternal grandmother’s skills, attentive and creative, and discovered that his mother resembles her. The externalized problem, re-narrated, allowed the emergence of a narrative not subdued by the history of conflicts in the period between the meetings. Aurora says:

A: The giant isn’t showing up much there... he’s only showing up with strength when he’s with his brother. They fight, Leo gets in the way, and Daniel loses his temper (the words giant and ghost will alternate during the course of therapy, as meanings of an entity/problem separate from the child).

T: I think it’s the Giant of Fury’s tricks to keep taking advantage of the fights in your family.

A: He (Daniel) is better than me, calmer than me, he obeys when I speak.

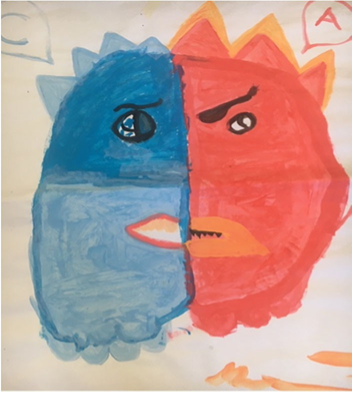

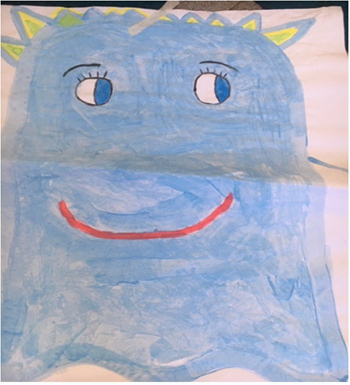

Despite the influence of the problem having diminished in the family, this meeting addressed many conflicting moments between siblings and between mother and children. Daniel suggests painting the Giant/Ghost again. Very excited, he announces:

D: Now I’m going to do it! It will have two colors. Half angry and half calm.”

The new image of the problem in metamorphosis was made with four hands, and the child tried to reproduce with his own lines the first form almost entirely created by Aurora (the Giant of Fury). This was explored in its finest details within a loving and respectful dialogue, mostly coming from the child. Everyone looked proud at the end.

Ghost of Fury in Transformation

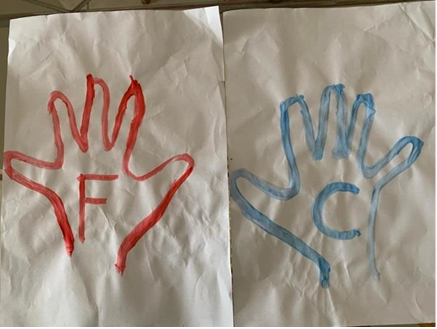

The letters C and A were added to signify the initials for Calm and Angry, English vocabulary learned by the boy at school. Descriptions and facts previously mitigated by the problem populate the conversations, allowing the child to be perceived through his resources (learns another language, likes to paint, collaborates with the mother). Immersed in a dialogical and horizontal relationship, instigated by conversations fueled by painting, I outlined Daniel’s hands on a blank piece of paper, with the letters F (Fury) and C (Calm) to be taken home. They could help them remember that when they manage to stay calm, the Giant weakens.

Drawings of Daniel’s Hands as signalers of emotions in the house

The session that followed this one focused on efforts to distinguish the influences of the Giant/Ghost in the family’s life and the family’s in the Giant's life. The rage attacks are less intense; frustrations are expressed with lamentations. Aurora says:

A: Daniel is more loving, more understanding, helping me to calm down faster. It was a lot of just complaining, now it’s like this, more smiling. Sometimes he is more patient with his brother.

D: I didn’t get angry with Leo crying. I say: ‘Caaaalm down, Leo’.

A: We put the Hands in the room. In a place where everyone can see.

T: If the house is calmer, how is the family?

A: I bought paints, they are painting.

T: It’s a family of artists!

At this time, they review the contributions of their maternal grandmother, skilled in manual arts. Daniel speaks proudly of his grandmother who draws house plans for engineers. Aurora has the opportunity to reframe her relationship with her parents, with whom she feels hurt by for not receiving the expected support: “My parents are very active, they have a life of their own...”

Daniel is attentive and praises his grandmother’s kindness but claims that his grandfather is very nervous: “The ghost must be living there now.” and continues... “Hey tía, I think next time the Giant of Fury will be all blue!”

From these conversations, another poetic document was presented to them at the next meeting.

It was a giant

Giant?

Not anymore

It wasn’t even a giant. It shrunk

And in its shrinking, OH! Would it also be changing color?

And the giant asked for help

Help! Somebody help me!

I’m shrinking and I’m not even red! Help!

And nobody listens

The artist mother and the smart boy continue their task of transforming him

Now the little giant is red and blue

Half bad, half good. Half angry, Half calm

The smart-mother and the artist-boy continue their work of painting the new little giant red and blue

The Giant of Fury is sneaking out

It no longer fits in that room. It no longer fits in those lives

At the door, already saying goodbye, he looks back and takes with him an image that bothers him. He sees the boy-artist calmly walking around the room, talking to his smart-mother, deciding together on the last brushstrokes.

The image has changed. And the Giant of Fury, sad, decides to leave in search of another place to live.

“The Fired Ghost of Fury,” Made by an Artist Upon my Request

When presented with the new image, this time taken by me, the mother laughs at the ghost and its “Fired” sign. Daniel says: “Poor guy,” and, “Mom, we’re firing him from home too!”

The self-confident artist-boy prepares to paint another ghost: “I do. It will be all blue. Blue is the color of calmness, right mom?”

Ghost of Calmness

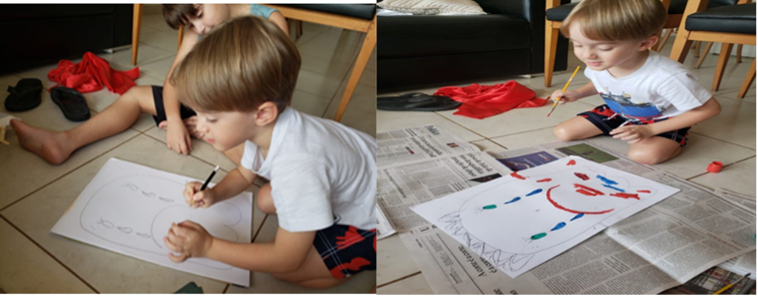

Since we were at that moment on the verge of social isolation due to COVID-19, we suspended face-to-face meetings and sought to build communication via WhatsApp, through messages and audio, since the video camera sessions proved to be unproductive for the participation of the children. Contacts were more frequently aimed at supporting Aurora’s concerns regarding Daniel’s growing lack of interest in online classes. Still, mother and son agreed that the Ghost of Fury was still diminishing. In this period of confinement, the interaction between the two children deteriorated, slipping easily into conflict. I suggested that Brother Leo be invited to participate in a face-to-face meeting, and we all committed to this meeting, respecting the health standards for disease prevention.

T: Hey! This is yet another trick by these evil Ghosts of Fury. He walked away and left his cousin in place.

D: Who?

T: The Ghost of Cry. He doesn’t let anyone play. He belongs to the Ghost of Fury’s family.

D: I know! I'm going to paint it at home! And it will be orange! We discovered one more trick of the Ghost of Fury.

T: These ghosts are very smart. They don't go away that easy. Sometimes they leave someone in their place.

A new conversation took the place of the turmoil created by the children. Leo asked his brother if he could help him paint the new ghost at home. A condition was placed by Daniel: “You can. But only if you don’t cry!"

“These two pictures were sent by Aurora, registering the moment of collaboration between the children “taking a picture of the Ghost of Cry’s face.”

She also used WhatsApp to send an audio of her externalizing conversation with her youngest son, about the Ghost of Cry. In the conversation established with the participation of the family, including the father, Leo said that he is very angry, screams like a bear, and eats boogers. He is calm when Leo is crying and gets angry when he stops because he likes noise. And when the mother says that she needs to send him away, he says: “But mom, he doesn’t walk, now he’s stuck in the paper!”

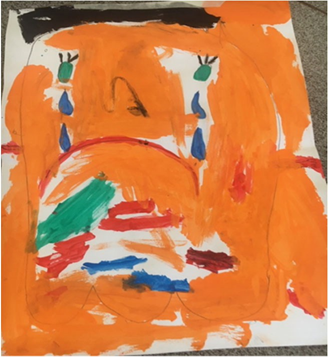

Ghost of Cry

We then established a way to stimulate the conversations about the problems, with the participation of Leo, through audios sent via WhatsApp, where I made some suggestions on how to deal with the new ghost that had just arrived. The boy-artist Daniel, now more collaborative and involved in actions that he would contribute to his parents and brother, suggested that this ghost needed to calm down.

Ghost of Cry in Transformation

This other “image” of the transformation of the Ghost of Cry was sent by Aurora and Daniel. The child’s audio explained that the green part is the calmness that makes the ghost stop disturbing. I asked if he (Daniel) had any part in this difficult task. Through the audio I heard: “I'm helping my mother to stay calm, tía.”

After many weeks of distancing, a second face-to-face meeting was decided, which would allow the participation of the father. The children were excited and, in my view, missed the meetings. They quickly turned the therapy room into a playroom. The room was populated with different toys and Daniel announced: “My father is good at Lego. When he has time, we play at home.”

In another article (César, 2012), I discuss playing freely in family therapy with children as a privileged opportunity in which they show solidarity and welcome the parents with whom they explore a collaborative world, dissipating intergenerational boundaries, and softening the shadows of the problems that brought them to therapy. One of the significant factors that contributed to family tensions was the weakening of the interaction between the father and the children due to the intensification of his work. Through Daniel’s hospitable hand, the father found an environment safe and relaxed enough to offer his children his unconditional presence.

At the end of this session, the boy-artist proposes another ghost to be externalized:

D: I already know who will be the next ghost when we get back!

T: The ghost family is growing!

D: It will be the Ghost of Play.

.png)

Ghost of Play with a Ball in Hand

This new character emerged in the next face-to-face meeting as a pictorial document relating to the ludic context in which the father’s presence was greatly appreciated by all. We understand that the Ghost of Play is like a guardian of the family that helps to keep calm, that’s why it’s blue. He likes to play ball in the square and makes everyone move away from the television. In this way, just as Daniel’s ghosts are metamorphosing from enemies to friends, is the child building, through his creative-reflective art, a communication that transforms his fierce issues into requests?

And aren’t externalizing conversations themselves a way of understanding through play, generating experience, producing changes, and accessing preferable selves for everyone involved in the conversations? And yet, from conversations about externalizing the problem, we were able to move into conversations that externalized solutions and hope: the ghost that calms people down and another that invites affective relationships through play.

In one of the phone contacts I had with Aurora, I sent a picture of the Ghost of Play and wrote: “Look who is here saying to me: Adriana, will Daniel accept me at his house? He loves to be distracted by movies on television, but I wanted to play ball with him!! I need to play with some kids today.” [Face-to-face meetings with the participation of Daniel began to take place on a monthly basis. Virtual contacts were maintained according to Aurora’s needs, but they were not enough to reassure her.] A few minutes later I received a message from the boy: “I accepted.” And also an audio: “Hi tía, (...) my father and my mother taught me to play tennis...”. Continuing the conversation, I replied: “Oh! Our Ghost of Play is certainly watching you play, having fun, and cheering for you!”

Other ghosts began to appear, like a certain Ghost of Complaint. The Ghost of Fury’s visits ceased, but the latter, a “cousin” of the former, kept confusing Daniel and led him to whine and make difficult situations where he would have to attend to his school obligations more promptly during the pandemic. This one not only imprisoned the children, but also managed to dominate the parents; he was no longer exactly evil, but rather, very tiring. In the meeting in which Aurora and Daniel participated, we reflected that such a ghost feeds on endless quarantines.

For Michael White, in the process of re-authoring:

People become curious about, and fascinated with, previously neglected aspects of their lives and relationships, and as these conversations proceed, these alternative storylines thicken, become more significantly rooted in history, and provide people with a foundation for new initiatives in addressing the problems, predicaments, and dilemmas of their lives.

Thus, re-authorship stories were continually created, despite the challenging routines experienced in the homes of families with children, in the face of this amazing and uncertain planetary event. Aurora learned to wait and welcome, and Daniel kept the presence of his ghosts alive by assigning them different levels of kinship. Its most feared member seems to be gone, leaving other less invasive, more friendly, and even generous in their place.

One of his observations made both to the discursive change about the problem and the relationships, and to the construction of shared solutions: “Oh tía, I think that in the family of ghosts, the Ghost of Fury and Ghost of Cry are brothers, like me and my brother, the others are cousins and have good ghosts and bad ones.”

It is important to clarify that face-to-face meetings, although sporadic, were opportunities for free and playful conversations, with the purpose of an affective (re)encounter for exchanging events and anchoring changes. An observation made by Aurora indicated a new position: “At home, it’s like here. We disagree a lot, but soon we calm down. The Ghost of Fury is gone and resolving complaints is easier.” In the midst of so many complexities, by allowing ourselves to be touched by the unexpected and be open to chance, we acquire eyes to look at enchantment.

The good ghosts became partners in family negotiations, careful advisors for new decisions by parents about their children's lives. And so, we said goodbye, knowing that a new ghost was about to arrive; he was yellow, and his specialty would be to complain: “All me, why always me??...” Thinking about the dialogic nature of playing as a conversational tool with children, Bakhtin (10) points to the possibility of creating something absolutely new, based on what is given. What is given is totally transformed into what is created and this transformation can be formidable...

Final Words

According to Grandesso (11), the main difference in the use of questions in narrative therapy is that they are made to generate experience instead of obtaining information. Freeman and Combs state that when they generate experience about preferred realities, questions can be therapeutic in themselves (12). Thus, from the curious openness to meet each ghost, we let ourselves be led, adults and children, both in face-to-face sessions and in virtual contacts, by creativity and mutual trust.The reader may wonder about the lesser participation of Leo, the youngest son, and the near absence of his father in family sessions. As there is no prior planning on how the therapeutic process will take place, but the path is built as you walk, the choices took into account the difficulties pointed out by Aurora and supported by Daniel, specialists in their own lives, desires, and hopes. Daniel’s changes helped to minimize the domestic stresses with his brother, an achievement sought by Aurora. We also held some sessions with the couple, so that they could talk about the adversities and obstacles faced by each one so that they could support each other as the protective system they hoped to be.

[Author’s Note: The names of the participants have been changed so that their identities are preserved, and as the author I obtained the consent of the family for the publication of this article.]

[Editor’s Note: This article, first published in the Journal of Contemporary Narrative Therapy, a free online journal (February 2024, Release, pp. 87-110, is reprinted here with permission of the author and founding editors, Tom Stone Carlson and David Epston.]

Questions for Thought and Discussion

What did you find most interesting about this clinicians’ work with this family?

Might you have done something different with this child?

What do you see as the benefits and challenges of using Narrative Therapy with children?

References

(1) Rodriguez, C. M. (2011). Aprendiendo terapia narrativa a través de escribir poemas terapéuticos. Revista de la Universidad Veracruzana, 7(1), 1–21.

(2) Paljakka, S. (2018). A house of good words: A prologue to the practice of writing poems as therapeutic documents. Journal of Narrative Family Therapy, Special Release, 49–71.

(3) White, M. (2012). Maps of narrative practice. W.W. Norton & Company.

(4) Epston, D. (2019). Re?imagining narrative therapy: An ecology of magic and mystery for the maverick in the age of branding. Journal of Narrative Family Therapy, 3, 1–18.

(5) Anderson, H., & Goolishian, H. A. (1988). Human systems as linguistic systems: preliminary and evolving ideas about the implications for clinical theory. Family Process, 27(4), 371–393.

(6) White, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. W.W. Norton & Company.

(7) Freeman, J. C., Epston, D., & Lobovits, D. (1997). Playful approaches to serious problems: Narrative therapy with children and their families. W.W. Norton & Company.

(8) César, A. B. C. (2012). Que linguagem é essa? O brincar em terapia familiar com crianças. In H. M., Cruz (Org). Me aprende? Construindo lugares seguros para crianças e seus cuidadores (pp. 71–89). Editora Roca.

(9) César, A.B.C. (2008). A externalização do problema e a mudança de narrativas em terapia familiar com crianças. Nova Perspectiva Sistêmica, 31, 85–98.

(10) Bakhtin, M. M. (1986). Speech genres and other late essays. (V.W. McGee, Trans). University of Texas Press.

(11) Grandesso, M. (2000). Quem é a dona da história? Legitimando a participação das rianças em terapia familiar. In H.M. Cruz (org). Papai, mamãe, você... eeu?: Conversações terapêuticas em famílias com crianças. Casa do Psicólogo.

(12) Anderson, H., & Goolishian, H. (1992). The client is the expert: A not?knowing approach to therapy. In S. McNamee & K. J. Gergen (Eds.), Therapy as social construction (pp. 25–39). Sage Publications, Inc.

[1] Brant, F., & Nascimento, M. (1988). Bola de meia, bola de gule [Song]. On Miltons. Sony Entertainment.

©2024, Psychotherapy.net

Adriana Bellodi Cosa César is a clinical psychologist and couple and family therapist who is certified by the ICCP (International Certificate in Collaborative and Dialogic Practices) by INTERFACI Institute, Brazil. TAOS Institute´s associate. Due to her passion for childhood issues, she has dedicated herself to independently researching clinical practices that enhance the care of children, both individually and in family therapy, for many years. Narrative, Collaborative-Dialogical practices and Reflective Processes are her theoretical and methodological inspirations. Creativity is the beauty and joy of putting all this knowledge into action.

Adriana Bellodi Cosa César is a clinical psychologist and couple and family therapist who is certified by the ICCP (International Certificate in Collaborative and Dialogic Practices) by INTERFACI Institute, Brazil. TAOS Institute´s associate. Due to her passion for childhood issues, she has dedicated herself to independently researching clinical practices that enhance the care of children, both individually and in family therapy, for many years. Narrative, Collaborative-Dialogical practices and Reflective Processes are her theoretical and methodological inspirations. Creativity is the beauty and joy of putting all this knowledge into action.

Adriana Bellodi Cosa César was compensated for his/her/their contribution. None of his/her/their books or additional offerings are required for any of the Psychotherapy.net content. Should such materials be references, it is as an additional resource.

Psychotherapy.net defines ineligible companies as those whose primary business is producing, marketing, selling, re-selling, or distributing healthcare products used by or on patients. There is no minimum financial threshold; individuals must disclose all financial relationships, regardless of the amount, with ineligible companies. We ask that all contributors disclose any and all financial relationships they have with any ineligible companies whether the individual views them as relevant to the education or not.

Additionally, there is no commercial support for this activity. None of the planners or any employee at Psychotherapy.net who has worked on this educational activity has relevant financial relationship(s) to disclose with ineligible companies.