Need Help?

Email or Call: 1-800-577-4762

Email or Call: 1-800-577-4762

Sign up for our

NEWSLETTER

NEWSLETTER

Need Help?

CONTACT US

CONTACT US

Ego Liberation: A Buddhist Guide to Escaping Your Mental Prison

Filed Under: Depression, Suicidality

Awakening

In 2016, I decided I wanted to become a therapist. After years of soldiering silently through unexplainable sadness, I found my way out of that headspace long enough to see hope for myself and others. I didn’t know what it meant to be a therapist at the time I enrolled in my master’s program. I had never really engaged in therapy before enrollment. But for some reason, I believed in the philosophical cure of self-discovery. Now I think self-discovery, on its own, might be part of the problem.for some reason, I believed in the philosophical cure of self-discovery. Now I think self-discovery, on its own, might be part of the problem

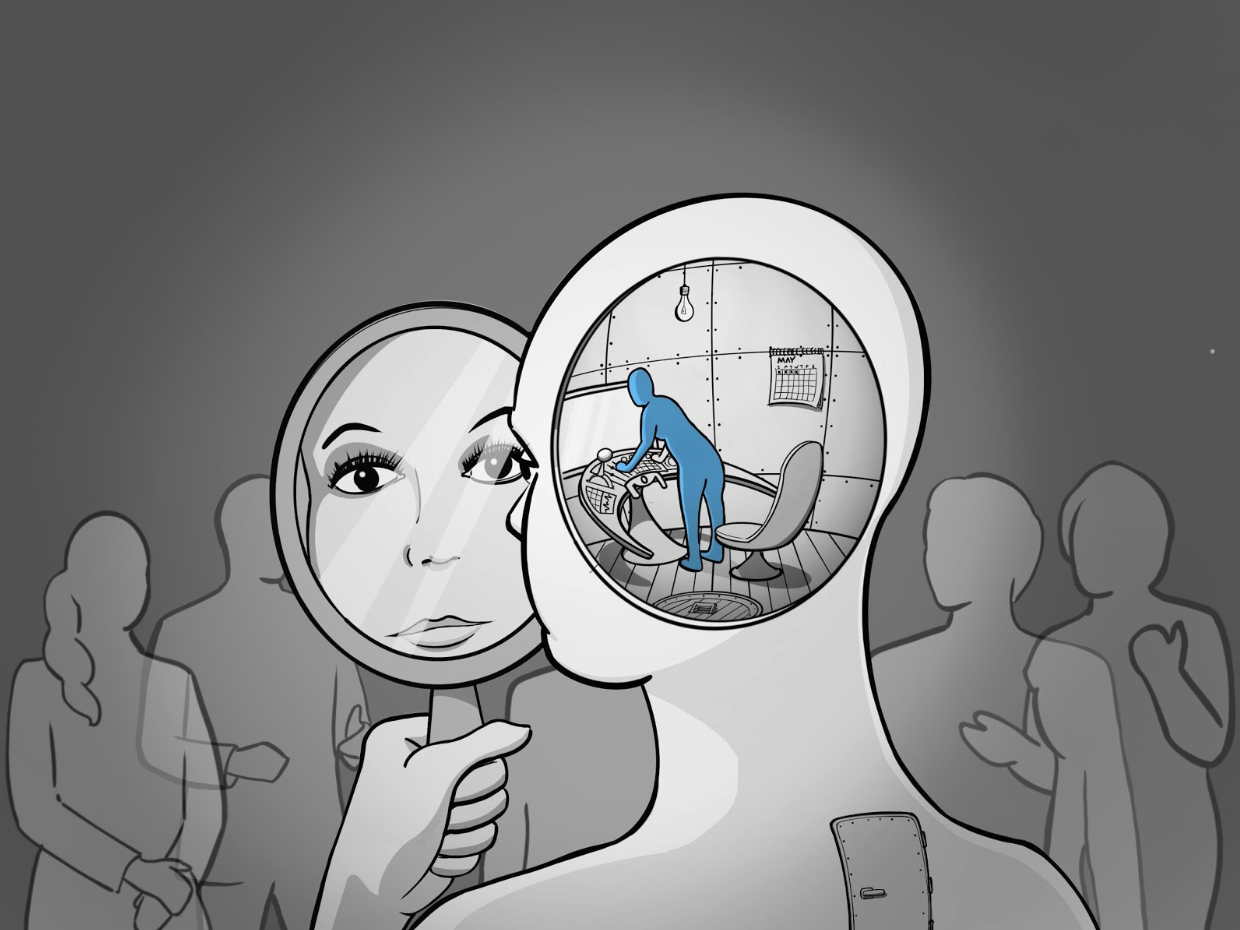

I used to equate therapy to individuation. And that’s partially true. Many therapists, including myself, use self-excavating questions and assessments to help people filter out expectational forces that keep us from “becoming who we are.” But as I’ve grown into this field, I’ve started to believe that self-defining and reframing tools have a limit in their helpfulness, and that perhaps the next philosophical remedy is not in ego defining but rather ego liberation.When I say ego, I’m not talking about narcissism or prideful thinking. I’m talking about ego as in our sense of self—especially a sense of self that is unchanging and completely autonomous and independent from our environment. I have found the ego has a way of limiting myself and the clients I attempt to help. I specifically remember seeing a student-client I’ll call Olivia, who was living with chronic and severe depression. Olivia wasn’t attending any of her classes, experienced regular dissociation and suicidality, and could barely muster the energy to leave her house. Unfortunately, our counseling services did not have the resources to assuage her advanced depression. I pleaded with her to look into more intensive treatment options. Olivia cried in my office and admitted she was resistant to trying anything new because she was afraid of who she might be without depression. She had no context for her ego outside of her depressive thoughts. I’ll return to Olivia later in this discussion.

We become comfortable in our own mental maze. Even if our maze is limiting and painful, at least we know how to navigate it. All behavior makes sense in context. A healthier sense of self can be reconstructed, but sometimes even that reconstructed self keeps us trapped. If we see ourselves as creative and smart, then what does it mean for us when we make a mistake?

Taking ourselves too seriously and wrapping our identities around positive attributes can have its pitfalls too

Taking ourselves too seriously and wrapping our identities around positive attributes can have its pitfalls too.Our sense of self also has universal implications when we consider how it impacts our understanding of common humanity. In an age of political, racial, sexual, generational, physical, gender, economic and religious othering, maybe the answer to our problem with power, oppression and polarization is not individuation. Our egos like to categorize our attributes and compare them to others, creating a feeling of separateness from our neighbor. It’s no wonder we’re exhausted from a continuous “us vs. them” dialogue. Perhaps there’s another way. Perhaps understanding the synthetic nature of our “self” is what we most need to feel more connected with others, less polarized and less serious about maintaining our identity

Freedom

Buddhist psychology and acceptance-based therapy invite us into recognizing the synthetic nature of our egos so that we may be free of the mental maze. This concept of the synthetic self or synthetic ego is what the Buddhists call anatta, or the doctrine of dependent origin¹. The main idea behind the doctrine of dependent origin is that the ego only feels real because the ego decided it was so. The ego is its own architect, and it desperately wants to be known and understood by others and itself. But the feeling we have of separateness from others and our environment is an illusion the ego creates to examine itself in relation to its environment. Mark Epstein, a famous Buddhist psychotherapist², often references this quote from a Mongolian Buddhist lama: “It’s not that you’re not real. We all think we’re real, and that’s not wrong. You are real. But you think you’re really real, you exaggerate it.” Buddhism attempts to break down that feeling of being really real and helps us see our person as it is, without attaching ourselves too much to our identity.Seeing through our illusory mental prisons of individuation allows us to explore the mystery of ourselves and not be so attached to the idea of our minds being separate and individualistic. Mindfulness and meditation help with this nonattachment to self. Being grounded and present with our physical world helps liberate the ego. The moment our minds wander off, we regress into autopilot and forget our connection with our environment. The challenge to escaping the mind is that we’re stuck in it. As Sylvia Plath, the famous poet, so beautifully pondered, “Is there no way out of the mind?”

Seeing our egos as illusionary is metaphorically akin to a dog chasing its own tail

Seeing our egos as illusionary is metaphorically akin to a dog chasing its own tail. How do we use our ego to liberate itself? This can be an especially difficult task in Eurocentric cultures and schools of psychotherapy, where the rugged individual archetype is widely understood and rewarded.I’ve found it helpful to look at the ego and ego liberation on three levels. These three levels are essentially stages of thinking and working toward seeing the synthetic ego. Because each level is predicated on the one below it, you cannot skip a level without experiencing the one below. However, people slide in and out of different levels as the mind attempts to deconstruct and reconstruct its own reality. These levels act as a spiral upward, with the level you experience operating in continuous existence with those below it. Meaning, if you are experiencing level 3, you are simultaneously experiencing levels 2 and 1. But you can experience level 1 without experiencing levels 2 and 3. Confused yet? Let me explain.

The first and most basic level of awareness involves perception and reality management. Imagine your ego sitting back in your head with a control panel, responding to and interpreting reality and holding the mind as an independent entity. That’s level 1 thinking. We tell ourselves stories about experiences and what our experiences mean for us. For example, when we experience pain, we may create a suffering story around that pain and tell ourselves, “This happens to me all the time because I’m worthless.” Level 1 thinking is always interpreting life and assigning meaning to life’s events. In many ways, level 1 is judging external events and people by making assumptions about the value, purpose and motivations of these external experiences. The level 1 ego is not self-reflective in understanding its own role within the judgements it makes.

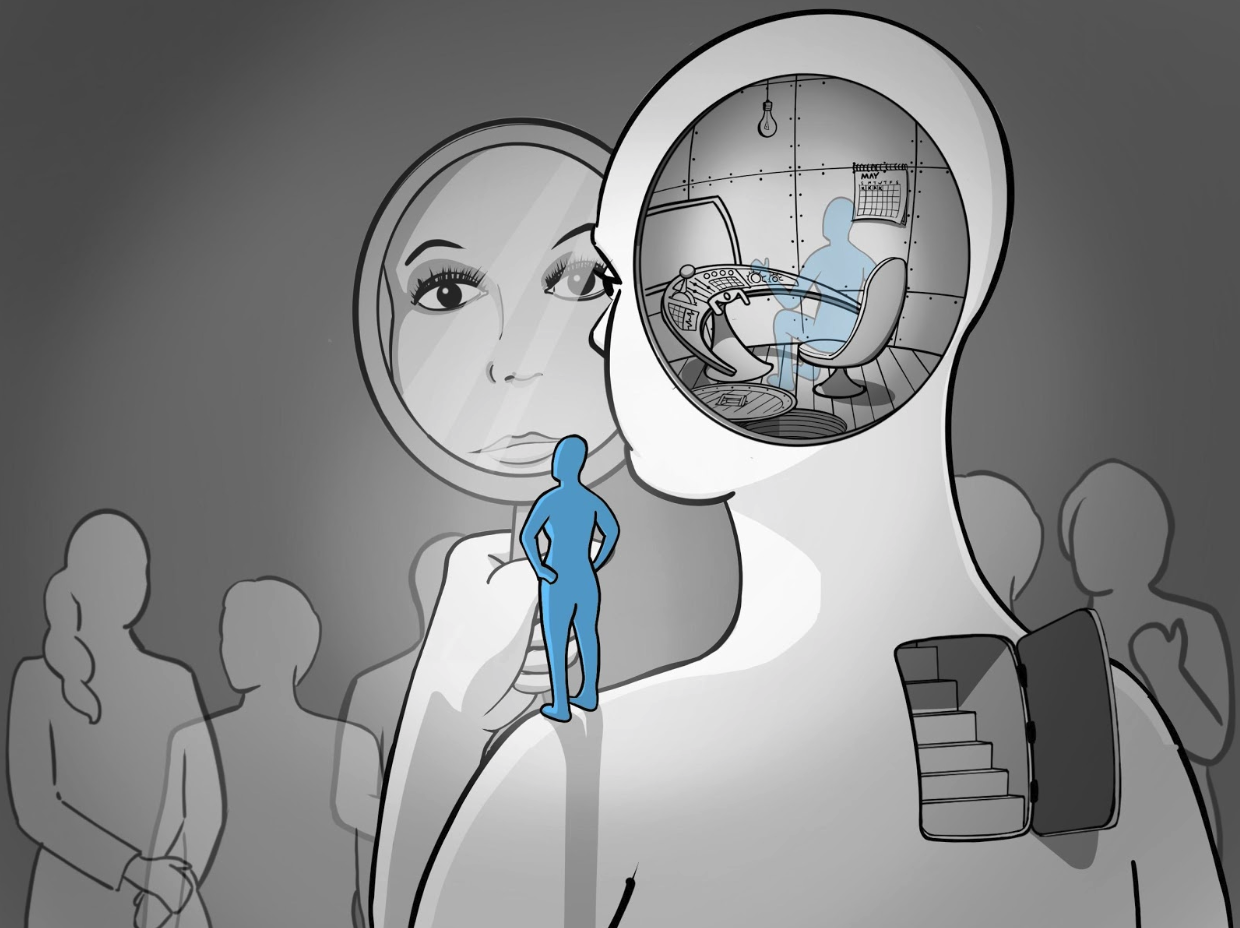

There’s a peace level 3 ego has in accepting the process and synthetic nature of level 1 and 2’s judgement and self-discovery. It understands and accepts the schema level 1 and 2 have built that create the synthetic ego. This understanding is the foundation of mindfulness. It’s the ultimate form of observation. Level 3 sees the purpose of level 1 and 2’s functioning and takes it a step further by integrating the self with the environment. Level 3 is feeling connected to everything. It is also finding the barriers between self and environment to be much more porous than previously imagined. The mindful observer understands that the self is much more flexible to behave and think beyond the barriers level 1 and 2 constructed through their analysis and critique of life and self.

Seeing the illusionary self and getting to level 3 is a long and sometimes arduous process. There are no shortcuts, and I’m not sure if anyone ever fully “arrives.” People must engage in some serious level 2 functioning and self-reflection before they can begin to conceptualize themselves as not being exaggeratedly real and separate. You can’t see the synthetic nature of yourself until you’ve first mapped out your ego’s identity through self-discovery. Jumping straight to understanding the synthetic self is impossible without first constructing the ego.

Identity is important, and it needs to be integrated within relationships and the environment

Identity is important, and it needs to be integrated within relationships and the environment.I constantly have to remind myself to practice mindful observation. Level 3 requires not just a philosophical understanding but, more importantly, an experiential understanding of equanimity through mindfulness and meditation. The goal is to behave in such a way that we understand our minds as being deeply connected and integrated with each other.

Olivia

Returning to my work with Olivia, integrating these three levels was essential to her movement toward a meaningful life. When Olivia saw me that day, she had already been engaged in level 2 work. She had reflected, constructed and analyzed all her behavior and thought patterns. Olivia knew her mental maze and was well aware of how her maze never served her needs. When she told me she didn’t know who she’d be without depression, she was really saying, “I don’t know if I’ll have an identity outside of depression.”I invited Olivia to consider the reality that her depressive thoughts and feelings were not her identity

I invited Olivia to consider the reality that her depressive thoughts and feelings were not her identity. I asked Olivia to consider the perspective that her depression symptoms were not the enemy. Olivia found this was a difficult reality to accept, especially when thoughts and feelings felt painful and overwhelming.I proposed that the goal of therapy should not be focused on fighting depression, but instead be redirected toward living a meaningful life while being depressed. For some clients, especially those with acute symptoms, this goal doesn’t sound like a good alternative. But for Olivia, a wave of relief came over her in considering living a life of meaning even if happiness was not guaranteed. This realistic goal is often a refreshing perspective for those with chronic symptoms, especially when the elimination of those symptoms seems unattainable. The non-judgment and acceptance that inform this goal are wrapped up in level 3’s mindful observation. It’s creating a different relationship with depressive thoughts and feelings, but not through a position of denial or naiveté. It’s accepting that the symptoms are there, acknowledging that pain, and acting according to your values without symptoms dictating your every move.

As Olivia became mindfully aware of her thoughts and feelings and accepted them without judgment, she began to free up mental space to be present in her school work, music and friendships. Olivia began to see her identity as tethered to her people, her hobbies and her environment through cultivating a commitment to meaning through action. The focus of her attention was no longer on the symptoms within her mind; instead, her focus was turned outward. This attention helped Olivia experientially understand her mind’s integration with others rather than see it as a self-contained, autonomous ego. We’re all hardwired for connection, and we need to step outside of ourselves to get there.

Through Olivia’s work in mindful observation, she approached her patterns and behaviors with more curiosity and mystery. Before, she felt locked in her self-constructed, unchanging identity. Oliva found a way out of that perspective, which gave her permission to exercise more psychological flexibility even in the face of unrelenting sadness. Olivia learned that not all thoughts and feelings needed to carry so much meaning; some thoughts and feelings are better off left alone through mindful observation.

I suppose that’s one of the greatest areas of discernment in psychotherapy -- when to self-reflect on thoughts and when to just leave them be. I can’t say there’s any matrix to figuring out that balance other than noticing when you’re becoming exhausted from self-examination and deciding to let thoughts be when self-examination isn’t serving you well.

Returning to Sylvia Plath’s and humanity's ubiquitous question, “Is there no way out of the mind?,” I believe we can find our way out

Returning to Sylvia Plath’s and humanity's ubiquitous question, “Is there no way out of the mind?,” I believe we can find our way out. I think we can be liberated if we choose to see our synthetic self. I think that liberation might help bring us back to each other. The sooner we realize that our brains embody and exchange energy and information through relationships in our environment, the more quickly we will understand the porousness of self and the interdependent nature of the mind³. With this understanding, we cannot help but find ourselves in a deeper place of compassion, empathy and common humanity.References

Mick, D. G. (2017), Buddhist psychology: Selected insights, benefits, and research agenda for consumer psychology. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 27, 117-132. doi: 10.1016/j.jcps.2016.04.003

Epstein, M. (2014). The trauma of everyday life. New York: Penguin Books.

Siegel, D. J. (2017). Mind: A journey to the heart of being human (First ed.). New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Illustrations by Drew Brandt.

©2020 Psychotherapy.net LLC

Adam Brandt, LPCA, is a licensed psychotherapist based in Raleigh, NC. He graduated from the University of Dayton and is currently working on his doctorate in counseling at North Carolina State University. Adam is interested in counselor faith integration, existential psychotherapy, Buddhist psychology and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). Adam’s clinical experience is primarily with college students and young adults.

Adam Brandt, LPCA, is a licensed psychotherapist based in Raleigh, NC. He graduated from the University of Dayton and is currently working on his doctorate in counseling at North Carolina State University. Adam is interested in counselor faith integration, existential psychotherapy, Buddhist psychology and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). Adam’s clinical experience is primarily with college students and young adults.

Drew Brandt (illustrator) is an industrial playground designer for Kid Craft in Dallas, TX. He likes making things, drinking water, and being active in the local roller derby community.

Adam Brandt, LPCA & Drew Brandt was compensated for his/her/their contribution. None of his/her/their books or additional offerings are required for any of the Psychotherapy.net content. Should such materials be references, it is as an additional resource.

Psychotherapy.net defines ineligible companies as those whose primary business is producing, marketing, selling, re-selling, or distributing healthcare products used by or on patients. There is no minimum financial threshold; individuals must disclose all financial relationships, regardless of the amount, with ineligible companies. We ask that all contributors disclose any and all financial relationships they have with any ineligible companies whether the individual views them as relevant to the education or not.

Additionally, there is no commercial support for this activity. None of the planners or any employee at Psychotherapy.net who has worked on this educational activity has relevant financial relationship(s) to disclose with ineligible companies.