I am pleased to offer you this lesson from my online couples therapy training program. It has been adapted from a lecture, and includes commentary from Michelle, our moderator, as well as comments from the audience. This will give you a glimpse into some of my principles for “Getting Off to a Strong Start” in Couples Therapy.

In this article, we’re going to focus on the following points:

- Getting Off to a Strong Start

- Three Types of Goals and Effective Goal Setting Questions

- Six Essential Elements of Early Interviews

- Developmental Change vs. Behavioral Change

- Identifying Vulnerable Feelings

Speaking of “strong starts,” let’s get going on our lesson…

Getting Off to a Strong Start

Ellyn: Today, we’re going to talk about getting off to a very strong and powerful start in couples therapy. And I’m going to teach you principles that have to do with both your mental set, so how you think about what you’re doing in those early sessions and how you position yourself with clients; and I’ll also be teaching some specific how-to’s. But this is not a cookie-cutter approach.

You will be looking at integrating pieces of this in the way that works for you, and also integrating pieces in terms of what is best for the kind of couple that you’re working with. I’ll highlight some of the pieces that work better with some couples and some that work better with other types of couples.

First, getting off to a strong and powerful start means you being a leader. By the time you’re finished with this course,

I want you to feel like you are a leader—that you are active in your work, you’re not reactive, and that right from the beginning you’re getting the couple’s attention.

I want you to feel like you are a leader—that you are active in your work, you’re not reactive, and that right from the beginning you’re getting the couple’s attention.

You’re establishing yourself as somebody who is strong, and somebody who understands and is able to help them. Also, they’ll know that they’re going to do the work and that coming to therapy is not waiting for you to wave a magic wand. If they will do the work, there is hope they can get out of the conundrum that they’re presenting to you.

The tone that you set from the very beginning is crucial and is based on the answers to the following questions: Do you see pathology? Are you looking for pathology or are you looking for developmental stuck places?

Seeing impasses as developmental stuck spots will help you and your couple be more optimistic. You’ll be able to inspire them that they, in fact, can overcome and can get out of their negative cycles.

Your style and what you pay attention to will indeed determine the direction of the therapy. I am always thinking, “How do I challenge my clients to develop themselves and to look at the development of themselves as something that is positive, that’s exciting, that can be rewarding and not something that’s a drudge or way too difficult for them to do?”

There are predictable reasons for why relationships fail. The primary issues that most couples struggle with are:

- There is a lack of development in either or both of the individual partners.

- They have a repetitive history of re-triggering emotional trauma in each other and not repairing it.

- They don’t have the ability to repair when they hurt or do damage to one another.

- They lack skills or knowledge.

Couples often don’t understand why they are struggling. They think that there’s something wrong with them or something is inherently flawed about their relationship. When you are thinking about the couple in front of you, the goals that you are going to set fall in one of three main arenas:

- The couple is coming to you for change, growth and development.

- They are coming to dissolve the relationship, to be able, in fact, to say goodbye to one another, to go through a divorce or separation, to get help with the kids and the parenting and in the process of separation to resolve any resentment so it doesn’t fester and impair their future relationship or their parenting.

- They need help making a decision. A common one is, “Should we stay together or separate?” Maybe one wants to have a child and the other one doesn’t, or there’s some kind of move or job promotion situation that’s creating enormous difficulty about whether they’re going to stay where they are or move. And of course, there is, “Shall we get married or shouldn’t we get married?”

You can slot each of your couples into one of these three areas as you begin to think about goals that make sense for them.

An effective couples therapist will, over time, become both decisive and incisive and be able to sustain positive momentum. So when the couple starts backtracking, or when they start getting bogged down, those are times that you want to intervene and intervene quickly so that you can keep the momentum moving forward in a positive way.

It is absolutely essential that you not get stuck in their negative cycles or allow their negative patterns to go on for a long time in front of you. You only need to see it briefly so you understand what they do.

Michelle: At that point, Ellyn might you point out the cycle that you’re seeing and explain it back to them?

Ellyn: Yes, I will point it out, because having a grip on the negative cycle is the beginning to disrupting it. It’s the first step of changing it. So as long as you’re sure that you’re not doing it in a negative, judgmental or critical way, pointing out their negative cycle can always be an effective intervention. What we’re going to look at a lot is the essential elements of early sessions and the whole process of goal setting.

Too many couples ignore their shortcomings and do not seek help until it is too late. Therefore you have people very often coming in to see you when they think it’s too late, when you might wonder if it’s too late—and indeed, sometimes it is too late. But the patterns have been going on a long time, and that’s why getting their attention and assessing with them whether they’re there to dig in and do the work is important. If the couple is ready to dig in and do the work, one of the things you want to ask yourself is do you have the time to see them? Do you have the time to work with them?

When I do a first session, I never do it shorter than a double session. It’s almost impossible to assess a couple, in my opinion, in a 50-minute hour. You’re talking about assessing two individuals and the relationship. Most of us would never spend just 25 minutes assessing an individual client, so I’m always asking people to come for a double session to begin with.

Usually when I’m getting started with a couple I want to see them frequently. I want to see them for a minimum of two-hour sessions, and this is especially true for those that are disorganized, hostile, fighting or on the verge of splitting up. It’s not a good idea to accept a couple who is in a bad situation if you’re not going to be able to make time for them in your schedule.

Essential Elements of Early Interviews

- Make contact with each partner

- Understand the problem

- Name feelings being experienced

- Empathically embellish those feelings

- Describe the destructive cycle, but…

- Set a clear direction… a way out (including delineating the importance of containment, repair and autonomous change)

- Define your role and your expectations for them

These essential elements are spread out through the first couple of sessions. The first essential element is making positive contact with each partner. That is, establishing the relationship and being able to understand the problem from each partner’s perspective. Sometimes it takes more work to understand it from one partner’s perspective than the other.

As you’re listening, name feelings that you’re hearing that are being experienced. Be able to empathically embellish them, to describe the destructive cycle and point out a clear direction for change. Delineate the importance of each partner containing their reactivity. Another part of the early sessions is defining your role and expectations for them as clients.

Making contact is something every therapist learns in psychology or counseling 101. One way to assess how hard it’s going to be to make contact is to ask your clients when they first come in, “How do you feel about being here even though we haven’t done anything yet?”

Their responses to that question will let you know who’s going to be easy and who’s going to be difficult to connect with. It’s a common situation for one member of the couple to say, “I’m so relieved. I thought we would never get here. I’ve wanted to come for a really long time. I’m glad we’re here,” and for another member of the couple to say something like, “I don’t believe in therapy. I didn’t want to come and I think this is just a waste of time.” It’s pretty obvious who’s going to be the harder partner to make contact with!

Other aspects of making contact include:

- Being friendly, kind and interested.

- Appreciating their anxiety. Couples therapy is more unpredictable than individual therapy.

- Acknowledging lack of control over what the other partner says or does.

- Hearing their story in the context of the structure you provide.

- Giving lots of positive strokes can be highly valuable in the early sessions.

Particularly, I like to highlight areas where I see a partner taking a risk, where I see them making themselves vulnerable and where they’re stretching themselves. I will do a lot of positive stroking of those aspects rather than focusing on anything that I think is contributing to their cycle. I also think it’s helpful to appreciate their anxiety.

Couples therapy is harder in many ways for partners to come to than individual therapy. They think to themselves, “It’s unpredictable what my partner is going to say about me.”

Couples therapy is harder in many ways for partners to come to than individual therapy. They think to themselves, “It’s unpredictable what my partner is going to say about me.” In individual therapy we have complete control over that, but in couples therapy they’re often anxious about what’s going to be revealed.

Another thing I would let the couple know is that I will provide a safe structure and context for them to tell me their story. So if the partner keeps interrupting or keeps saying, “No, it didn’t happen that way,” I’ll say, “Wait, stop. I want to hear the story from each of your perspectives.” I want to get the whole picture and not let them be interrupted by the other one.

Michelle: Can you say a little bit about the beginning of the session when you ask them the question, “How do you both feel about being here?” and one person seems motivated and the other one not? Can you tell me what you do with that information? Do you orient the sessions differently?

Ellyn: Yes. When one person says they’re motivated and the other person says they’re not, I know it’s going to be essential for me to make contact with the partner who’s not motivated. I’m going to be especially observant about how I make a connection with that partner.

Sometimes making that connection might be as simple as saying, “I’m glad that you came in today. Do you know that you can come to couples therapy and not have to change anything about yourself?”

Sometimes making that connection might be as simple as saying, “I’m glad that you came in today. Do you know that you can come to couples therapy and not have to change anything about yourself?” Because they are so afraid that the focus is going to be on them and that they are going to be required to change. You will always have better buy-in for homework with the motivated client. So I am less likely to give the unmotivated client homework until I have a stronger connection with them.

I’m working to understand the couple’s problem both cognitively and affectively. The problem that they are bringing to me is usually understandable based on a couple of things: It’s understandable and predictable based on the attachment style of each partner. It’s also predictable based on the developmental stage. For example, if the couple has been together more than two years and they’re still stuck at the symbiotic stage, that’s going to be a problem, and that’s going to require them to be able to work in the area of differentiation.

The problems that they’re coming to you with will be a function of their arrested development—and once you have a full understanding of our Developmental Model of Couples Therapy, you’ll be able to describe that to them. It’s also predictable based on how long the partners have been together. A couple that’s been together just six months is not going to have any effective differentiation and I can’t possibly expect that they would.

On the other hand, with a couple who’s been together for 10 years, has a chronic history of conflict avoidance and has never differentiated, I know that it’s going to take a lot of risk, push and challenge for them to get out of that if they’re going to change the core dynamic of their relationship. Part of understanding the problem is asking helpful, insightful questions. In that process I want them to begin to think more deeply about what they’re saying. I also want them to understand the problem from an emotional or affective standpoint, so I’m going to be feeding back a lot of their feelings as well.

Here is an example of how you might describe a destructive cycle. I made it a little more complex than you might with most couples just to put a variety of both feelings and behaviors into it. I might say to Sally, “When you feel hurt by something that Ted says, it’s difficult for you to tell him that you’re hurt or to request an apology. Instead, when you feel hurt, a part of you wants to hurt him back so you tend to criticize him.”

Then to Ted I might say, “When you feel criticized by Sally, your tendency is to disengage and withdraw. Sally then ends up feeling lonelier, and instead of the two of you being able to repair and reconnect, the cycle keeps escalating. It keeps repeating and each of you is left in pain.”

Then I might ask them how they’re responding to what I’ve just said. And I look for their non-verbal cues, as well, to see if they agree with me. Are they connecting with what I’m saying, and does it make sense to them? Then you are able to not only connect with their feelings, but empathically embellish on them even more. The more you empathically embellish on your clients’ feelings, the more understood they’re going to feel, and the more able you’re going to be to confront that partner later on.

I want to have those moments of good empathic connection early on. Those might come from commenting on their deep loneliness or their helplessness, or you might say to a client, “You have tried and tried. You’ve tried everything and you’ve been really stuck, because nothing at all is changing. In fact, it looks to me like at this point you’re beside yourself with frustration and you wonder if there’s even a way out.”

A lot of people will nod their heads or begin to cry. They really know that you know how hard it has been for them, because they have been trying. And they didn’t know what to do. They didn’t know how to get out of that stuck position. So they might feel like you get and understands them.

Michelle: A lot of couples at that point will also say, “Yes, you’ve got it.” Their anxiety will come up and they’ll say, “Okay, so what do we do about it?” And they’ll want to move fast at that point.

Ellyn: Right. And because they want to move fast, that can actually be a good bridge to goal setting. It’s not enough to be understood. I know that it is going to take change on the part of each person to change the dynamics between them. So I’m going to spend some time now talking to you about goal setting.

When you hear the words “set goals,” it’s so prevalent in our culture that it sounds like it should be something easy to do. And yet

to do good goal setting with couples is an incredibly sophisticated and complex skill that takes time.

to do good goal setting with couples is an incredibly sophisticated and complex skill that takes time. It’s usually integrated into several sessions. It’s not something you can do in just one session unless you have an incredibly insightful couple who’s been in therapy before and they know what they want to do.

The more disorganized the couple is or the more hostility there is, the more challenging it’s going to be for you to arrive at effective goals. And I want you to come away from this lesson actually being able to reflect on the couples that you’re seeing and really ask yourself, “In which of these cases do I have strong goals that make sense and that will help move this couple forward?”

If your answer to yourself is, “I don’t” for any particular couple, then you can back up and say, “This is a good time to reassess. Let’s see what we can look at as the next goals to undertake.” One of my favorite cartoons is of two couples talking in one couple’s living room. One says to the other, “The work being done on your marriage… are you having it done or are you doing it yourselves?”

The reason I love this cartoon is because so many couples wish that the work would be done for them. They come in either hoping that you have a magic wand that you’ll wave to change their partner or that they can sit back, wait and watch for their partner to change.

That’s why the skill of getting each person invested in changing something about themselves that will move the relationship forward means that you’re dealing usually with character issues in each partner. You’re also dealing with motivation issues and possible resistance to therapy issues.

What is an effective goal? To me an effective goal is one that requires an individual to do some self-reflection and self-confrontation. And you’re asking the couple about their values and you’re implying that a change is needed in their pattern of reactivity. You’re asking them to self-select some new standard of behavior and to hold themselves accountable to whatever the change is that they are working on.

One way to think of the change needed in their reactivity is to think about what this person needs to stop doing in order to create the space for change to occur. You might think about it in terms of what this partner needs to start doing, or what both of them need to do differently that would enable them to take risks and move themselves forward.

Michelle: Ellyn, do you ever explain to your couples the concept of making a shift within themselves? I think that’s counter-intuitive to most couples when they come in, because they believe the problem is with their partner.

Ellyn: Yes, I do, and one of the things I talk about with some couples is the principle of autonomous change. What I mean is, not saying, “I will only change if you change,” which is a common thing that partners do—they tie their changes to whatever the other person does. I tell them, "If you make changes regardless of what your partner does, you will be able to have a very rich learning opportunity, because as you make changes, you’re going to see what unfolds; you may be very pleasantly surprised by the changes that start to occur, or you may find that your partner does nothing." Saying something like that is actually directed at both partners, including the partner who may be inclined to do nothing because they’ll realize that it’s going to be observed if they, in fact, are doing nothing.

A good solid goal will be clear and it will contain action and behavior. You and I know some about the intrapsychic change that’s behind any particular behavior, but by putting it in behavioral terms for them it becomes concrete and somewhat measurable.

When you’re looking for these changes in behaviors and actions, you’re also looking at whether the person has a real motivation to accomplish them. If there’s no motivation to change, it’s a useless goal and not one that I want to accept.

If somebody says to me, “I should pick up more clutter. I should pick up after myself,” I might say back to them, “I wonder how badly you really want to do that. Is that something you want for yourself or something that you think somebody else is telling you that you should do?”

Usually they’ll say, “I’m getting so much criticism from my partner that of course I think I should do it.”

And I might say back to them, “I wonder how picking up would be helpful to you. Is there anything that you can see that would motivate you to begin to pick up more?”

That can go into a 20- or 30-minute conversation until you get the piece of motivation that would genuinely be motivating for that partner to start to clean up more clutter. You’re always looking for goals that are individually focused, not dependent on what the other person does. The goals can be contradictory, and by that I mean even as extreme as one partner saying, “I’m here to get help with ending this marriage and I’d like to do some of the steps that are involved to end this marriage in a good way.” The other person might say, “I’m here to build a positive marriage and I do not want this marriage to end.”

Even though these are such contradictory directions that will create anxiety in the room, they are genuine for each partner. And then you can figure out what that literally means for each of them to be able to carry those goals out. Always remember that knowing the presenting problem is not a goal. Typically, couples will say things like, “We have a communication problem and we need to communicate better.” Nothing about that is a goal.

Don’t assume you have goals and objectives when you know the presenting problem.

Don’t assume you have goals and objectives when you know the presenting problem. When you ask most couples why they are there, the typical response is a description of their partner’s failures, shortcomings and things they do badly. They want to get relief by having their partner make the necessary changes. It’s very rare for them to describe to you what they need to do in order to strengthen the relationship.

Over the years I’ve challenged myself to come up with lots of different ways of setting goals with couples. I’ve used lots of different kinds of questionnaires, and I’m encouraging you all to experiment with what works for you in your practice and what works with different kinds of clients.

One very simple form instructs them over the week to go home and answer the following five questions:

What type of relationship do you want to create? I give them examples to help get them started: “You might say you want to create a loving intimate relationship, a relationship with a lot of team work. You might say you want a more companionate relationship.”

How do you want to be as a partner? This is asking for a frank self-assessment. How do they in fact want to be? Do they want to be somebody who makes time for the relationship, somebody who wants to negotiate solutions that are working for both people? How do they want to be in their day-in-and-day-out life?

What do you want to learn about yourself or the relationship? This is a request for cognitive knowledge that each partner would like to obtain. An example would be understanding your patterns as a reflection of some early childhood experiences.

What do you want to stop doing? Common examples are blaming, name-calling, withdrawing, or avoiding conflict.

What do you want to start doing instead? In evaluating responses to this question you are looking for constructive behavior that each partner will do when they stop doing the behavior that is contributing to the negative cycle.

Before I have people take it home and fill it out, I give them some examples of answers. A lot of times people will say things like, “I want to stop blaming and criticizing. I want to start giving my partner more positive strokes. I want to start saying what I appreciate and I want to start looking for more win-win resolutions.”

I ask them not to share their answers with each other until they come back the following session. Then I have them read their responses to each other and we work at refining what makes sense as a goal. You can also use this form to assess their progress as you go through the next few weeks.

Here’s another questionnaire I sometimes give couples as homework:

- What do I want to learn or understand?

- What do I want to stop doing?

- What do I want to start doing differently to build a more loving, giving relationship?

- What is most urgent for me?

One couple, Cindy and Jack, answered these questions. When they came back here’s what they had written:

Jack said, “I want to learn where my blind spots are that come from my family of origin. I want to stop withdrawing, and start being less defensive. It’s urgent that I be more able to do what I want to do.”

Cindy came back and said, “I want to learn about where I get stuck in loving my husband. I want to stop being like his mother and accept that I am his equal. It’s urgent that the abundance in our relationship continue.”

What do you think is wrong with these goals?

Participant: I think that neither one of them actually said something concrete about what they could do. They talk about what they want to happen, but they aren’t coming up with anything concrete that they could do.

Ellyn: That’s right.

Participant: “Learning my blind spot” might be necessary to understand and to stop withdrawing, but under what circumstances or how would he do that?

Ellyn: That’s right. There’s nothing concrete here; it’s vague. You don’t get a sense of what they’re going to do. With Cindy we don’t have any idea of how she might be like his mother and why it would be important for her to stop being like his mother.

When you ask the question about what’s most urgent, urgent usually has a timeline, not something so open-ended as wishing for “the abundance in our relationship to continue.”

When you ask the question about what’s most urgent, urgent usually has a timeline, not something so open-ended as wishing for “the abundance in our relationship to continue.”

For Jack, you can’t picture what he really means by being less defensive. And when he said that it’s more urgent that he be able to do what he wants to do, I wanted to know what kinds of things he wants to do. When I pursued that with Jack, he felt like it was completely impossible to spend any of his non-work time away from Cindy. When we began to define it further, one of the things that was urgent for Jack was to have the ability to have some individual time alone each week. And then it went even further that he wanted to be able to take some golf lessons. So we were getting into something that could disrupt the intensity of this enmeshed, conflict-avoiding couple.

Next Cindy started to refine her goals and it shifted to, “I want to understand why I feel depressed when Jack and I disagree. I want to stop walking out of the room when we have a disagreement. I’d like to learn how to talk through a conflict from beginning to end, and be willing to listen to Jack’s side. And it’s urgent that I stop catastrophizing conflict to mean that the marriage is over.” She was a very conflict-avoiding partner who was fearful. She would become extremely anxious at any moment there was conflict and because she would get so anxious she would leave, disengage, or get out so that the conflict couldn’t surface. She was terrified that conflict would end the marriage.

I talk about the principle of character a lot with couples: when you’re in a committed partnership, it tests your character. It tests your character in a way that most other relationships don’t test your character. It’s easy to be nice, warm and loving when you fall in love with somebody. And it’s easy to be nice, kind and loving when everything is going right. But when your partner acts like a human being, do you get indignant?

Do you get incensed that your partner is human and has normal flaws? Can you accept that maybe your partner gets a little anxious and testy if they think you’re going to be late for an airplane? Or if they’ve had two or three cranky kids all day long and feel spent, when you walk in the door and they don’t say “hello” to you in the best possible way, can you give them a break? Can you be forgiving?

The Three-Circle Exercise

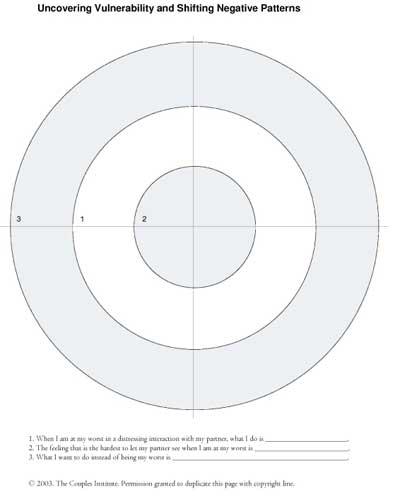

To finish up this lesson, I am going to give you one more concrete way to set goals. At the end of the article, you will find a diagram with three circles, called “Uncovering Vulnerability and Shifting Negative Patterns.” This three-circle exercise is a way to establish more effective goals.

I ask partners, “When you are at your worst, how do you act with each other?” Sometimes I’ll even brainstorm a list and put it on a white board that I have in my office. We’ll create a little list of things like “get critical, blame, yell and break things.” Encourage them to tell you what they do when they’re at their worst. I choose four of the items in this list and write them in the circle diagram.

The next part is tricky.

Ask them to tell you the emotion that is hardest for them to show to their partner when they’re at their worst. When they’re at their worst the way that they act is covering a more vulnerable feeling.

Ask them to tell you the emotion that is hardest for them to show to their partner when they’re at their worst. When they’re at their worst the way that they act is covering a more vulnerable feeling. In this particular case one client said, “When I puff up and get grandiose I’m covering up fear.” We worked to get to that. “When I break possessions I tend to be hiding the fact that I feel a lot of shame. When I scream and escalate it’s usually covering up the fact that I feel inadequate and helpless. When I yell, I don’t want my partner to see that I’m feeling very vulnerable or fearful.” Write four of their answers in the second circle diagram.

Then circle number three is designed for what they want to do instead of these things. When they’re at their worst, what do they want to shift that will make a definite change in the relationship? And here what that client said was, “What I want to do instead is I want to say that I’m frightened, be able to admit that I did something that may have been stupid and unthinking, and know that that’s just human. I also want to be able to take deep breaths and be able to take a timeout.” And the last one was, “I want to be able to say ‘I don’t know how to help you now,’ to my wife.”

I sometimes ask clients to take these diagrams home and post them somewhere that feels comfortable: somewhere they can look at them and refer to them. It gives you a wonderful tool when they come back and they’re talking about having had a difficult fight or difficult interaction. You can ask, “Where does it fit on here? Were you able to stretch at all? Were you able to do something new? Were you able to take a risk? Were you able to show your fear? Were you able to show that you felt vulnerable?” This is a powerful way to set some effective goals.

One way to know if your goals are effective is to see if the partners begin to grow and change. Over time they’ll assume new roles with each other, new responsibilities, and new ways of being. And the relationship will begin to move through its stages of development and become increasingly more interdependent.

I want you to ask yourselves, “Is there noticeable change in the couples and partners I’m working with or are they just spinning their wheels?” If they are spinning their wheels I would say it’s time to go back and reset goals with them. Couples work is one of the most rewarding, wonderful things you can do with your time and it will always challenge you to stretch and grow. It is not for the faint of heart.

Copyright © 2010 Ellyn Bader, PhD.